In our last survey, we found that 41% of our readers’ main portfolio strategy is buying and holding individual stocks. The most common suggestion when asked how we can improve Market Sentiment was to introduce a section where you can get exposure to new companies and industries.

To do this, we are interviewing some of the top hedge fund & mutual fund managers to dive deep into their highest conviction ideas. These investors have already spent weeks and months building conviction in their idea before investing.

With that, we are interviewing Jacob Rowe this week, founder of Rogue Funds, a small hedge fund based out of North Carolina focusing on value-oriented and special situation stocks.

Quick Facts

Fund manager: Jacob Rowe

Fund: Rogue Funds

Established: Q2 2023

AUM: ~$2 million

Unaudited returns (net of fees since inception): +57% (S&P 500: +38%)

Company in focus: ASP Isotopes (NASDAQ: )

Hi Jacob, thank you for doing this interview. Can you please tell our readers a little more about your background and how you started Rogue Funds?

Sure thing. I started investing when I was 14 after reading 'You Can Be a Stock Market Genius' by Joel Greenblatt – that's what kicked everything off for me. Like many investors, I tried my hand at swing trading early on, but that didn't work out so well.

After graduating with a mechanical engineering degree and working in aerospace for a bit, I started building a track record portfolio in 2022. Things went well, and by May 2023, I was ready to launch the fund. While I was supposed to start with five investors, I ended up launching with just one who put in $100,000. From there, we've grown to manage a bit over $2 million today.

By focusing on distressed opportunities and spinoffs, we aim to identify companies that are undergoing significant changes and offer the potential for high returns. Our approach is characterized by a concentrated portfolio of high-conviction investments, backed by rigorous research and analysis.

We take a value-oriented approach, seeking to purchase assets at a price lower than their intrinsic value, and holding on to them until their value has been realized. Since our inception last year, the fund has returned 57.4% compared to the 38% return of the S&P 500.

Congratulations on your success. Why did you go with a hedge fund model? Why not an ETF?

I’ve always wanted to run a hedge fund. I think the fee base for performance is a lot friendlier, whereas most ETFs are just an allocation game. You just try to get a large allocation subset. With ETFs, you also have to deal with redemptions — I've never had a redemption – all my investors have stuck with me. I’m going on a year and a half now and I’ve had exactly one investor that said in a few years they might need a redemption.

Also, by running a hedge fund, I can have a personal relationship with my investors that I can’t have with ETF holders. This helps when I am making a new investment and makes it easier to convey all the risks associated with that investment.

Great. What’s your research process like? How is your filter set up to find distressed opportunities that traditional investors miss?

My research process starts with several screeners, including low price-to-sales ratios and a modified version of the magic formula. Being a smaller fund gives me more flexibility, which allows me to be highly selective. I'm not looking for modest returns like one or two-baggers over five years – I'm searching for potential 20x returns.

I review thousands of companies, and over time, I've developed the ability to quickly eliminate opportunities that don’t meet my strict criteria. This efficiency comes from evaluating companies based on their valuations, growth prospects, and other key metrics that align with my investment goals.

What’s the most interesting idea on your radar now?

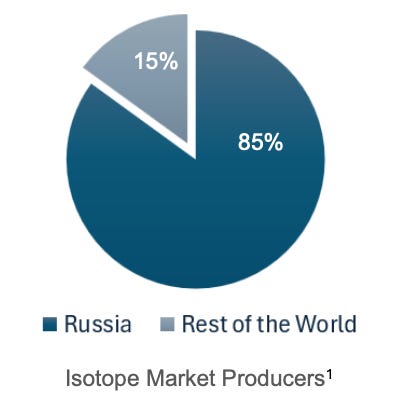

Our highest conviction position is ASP Isotopes , a nuclear enrichment company that I believe is significantly undervalued even after its recent price appreciation. The company operates in a critical space where Russia has historically dominated the market since the '90s when they flooded it with enriched materials from decommissioned nuclear weapons. With Russia now facing U.S. sanctions, there’s a major supply gap emerging.

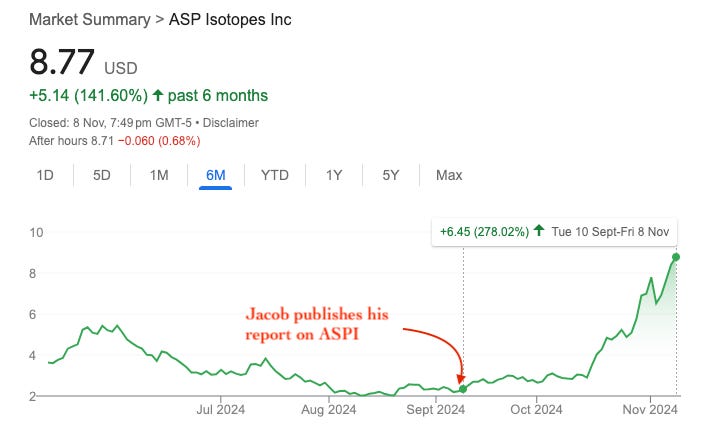

Congratulations on making that call. I saw you were one of the first to analyze the company in September, and it’s now up 278% in 2 months! Can you explain what the company does in simple terms? Is it still a good opportunity?

Let me break down what they do in simple terms. Take carbon for example – every carbon atom has 6 protons, but it can have different numbers of neutrons. Carbon-12 has 6 neutrons, Carbon-13 has 7, and Carbon-14 has 8. These different versions are called isotopes, and adding those extra neutrons changes the physical properties of the atom.

To see how valuable this process is, a kilo of Carbon-12 (Charcoal) only costs $1. But a kilo of Carbon-14 costs $24 million!

The challenge is that useful isotopes are incredibly rare in nature - sometimes only one in a trillion molecules. ASP Isotopes’ job is to increase the concentration of these valuable isotopes. They do this using two technologies: one that's like a super-fast centrifuge, and another that uses lasers to identify and extract specific isotopes.

Deep Dive into ASPI Technology — Corporate Overview Deck

As for the valuation, even at the current market cap of $500 million, I think we’re still in the early innings. Their biggest competitor, Centrus, won’t be producing HALEU (High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium – The fuel used in new nuclear reactors) until 2032, and they need billions in capital expenditure. ASP only needs $100 million per plant and could be up and running by 2027. This gives them a potential five-year monopoly in a rapidly growing market.

The recent 200% jump was primarily driven by two events:

Proving their laser enrichment technology works (which was a huge technical risk that's now behind us) — Source

Securing a contract with Terra Power — Source

These developments significantly de-risked the company, but I believe the market still hasn’t fully appreciated how important eliminating the technology risk was. With revenue expected to start flowing in Q4, a potential HALEU license coming soon, and their capital-efficient approach, I think they could reach a billion-dollar valuation much sooner than most expect.

What's your hypothesis on valuing the company given that it’s pre-revenue with a $500M market cap?

At the end of the day, valuation is an estimate of future cash flows. I mean, that's what it is. Anyone who says they can put a solid number on a pre-revenue company is a liar – just outright. Unless there are already contracts in place, which doesn't always mean anything either, you should always play it safe on your valuation until that revenue starts coming in and you can actually see it.

That said, what makes ASP unique is the multiple paths to significant revenue. Once they start uranium enrichment, they could go from zero to $300 million in revenue almost overnight. Paul (the CEO) expects 70% gross margins across the board, which makes sense given what we see from other enrichers and the fact that they're the only ones who can do a lot of these isotopes right now.

Their capital efficiency is also a huge advantage – they need $100 million per plant versus billions for competitors. And much of this capex isn't even coming from them – Terra Power is paying for their HALEU facility, which significantly reduces the risk.

You also have to consider the macro backdrop where Russia's been basically monopolizing enrichment since the '90s. Now with sanctions, Western companies are scrambling for alternative suppliers. ASPI is positioned to be one of the few viable options, especially in the HALEU space where they could have a five-year head start on competition.

The recent technology validation and Terra Power contract weren't just good news – they fundamentally de-risked the business. I think the market hasn’t fully processed how significant these developments are.

Personally, when we were looking into the company, we found three red flags:

The company seems to be spreading itself too thinly across various industries by trying to get into nuclear energy, medical applications, AI Silicon chips, etc.

The CEO diluted once again after repeatedly stating that they were done with dilution and would raise future funding via debt.

There was a short report by J Capital in Feb ’24

What do you make of this?

]]>This week’s guest is Brad Freeman. Brad writes Stock Market Nerd, a free newsletter focused on company deep dives, earnings coverage, and general stock market developments.

You can follow his thoughts or connect with him on Twitter.

Hi Brad, thank you for taking the time to do this interview. Excited to have you here and congratulations on hitting 100K followers on Twitter. Your account is one of the most informative ones out there — Can you please tell our readers a little more about your background and also about Stock Market Nerd?

Thanks for having me! I’m a 26-year-old who has just always had a fascination with studying different businesses. I graduated from Michigan in 2019 and got my Masters in Finance degree there last year. I worked at a small registered investment advisory firm (called Diversified Portfolios in Metro Detroit) for a while, before falling in love with turning my company research and analysis into writing. To my surprise, there was a ton of interest on Twitter and what started as having fun chatting through things with a few folks really exploded into something I’m surprised by and grateful for. I briefly wrote for Motley Fool but was determined to go out on my own to gain full control over content creation.

Since beginning to publicly track my performance in July 2022, I am up 17.11%. This is well in excess of the S&P 500’s returns over the same time frame but lags the Nasdaq by a small, shrinking margin as I’m less exposed to mega-cap tech than that benchmark is.

It’s interesting how you decided to go out on your own so early! How much of your portfolio is invested in the stocks you are bullish about? How much is allocated to broad-market index funds?

100% of my funds are available for single-stock investments. 5% is in cash with the other 95% in holdings. This is a byproduct of being 26, having no children, and enjoying disposable income. I’d expect my allocation to shift partially towards indexes over time as responsibilities grow and I age.

You made an incredible deep dive into Shopify – what made you focus on that particular company and how do you pick companies for your deep dive?

It goes back to that fascination with businesses. I love studying businesses and some are more interesting to learn and master than others. That’s what drew me to writing about Shopify as there’s so much going on under the hood of the company. What’s labeled as a web builder is so, so much more. This is generally how I pick companies to dive into. They’re usually holdings or companies I’m interested in holding at some point and that I’m excited to read about. When you’re digging through all available filings and document archives, it’s important to pick a firm you’re excited about so you can stay motivated. Fortunately, I find a wide range of sectors interesting.

What made you get into investing and what’s your investment strategy? Which industries do you focus on?

My dad got me passionate about stock picking from a very young age. He taught me to read financial statements before I knew how to drive a car. I focus on disruption and innovation in the broadest sense. Within that, healthcare, advertising, FinTech, security, and the app economy are key themes in my portfolio. My largest 5 holdings are Meta, Duolingo, SoFi, Progyny, and Lululemon.

What’s your best learning over your investment career? Can you tell us a bit about how your mindset toward money and investing changed over the years?

There’s no one size fits all. There will be bright people everywhere telling you how successful they’ve been within their own niche. What works for them is likely not what works for us. It’s important not to copy, but instead to explore and hone in on what works best for you. Structuring an approach that lets me sleep well at night while participating in the secular growth trends in our world is vital to me and guides my processes. “Responsible pursuit of disruptive growth” is a decent label.

What’s your research process like? What are some common red flags and positive signs when researching a company?

My research process involves reading recent annual and quarterly filings, earnings/investor day/conference transcripts. I consume all relevant public info available. It’s important, however, to also glean insight and data from sources besides a firm’s leadership team. These teams are inherently motivated to paint a rosy picture, and vetting that view with vendors like Gartner, SensorTower, etc. can really help to be confident that the picture is actually rosy.

Red flags:

Excess management turnover.

Accounting blunders and shady off-balance-sheet items.

Excess financial leverage.

Shrinking margins over a long period of time.

Plummeting growth (gradual slowing is inevitable).

Egregious dilution and executive compensation practices.

What’s the best investment decision you have made? And one investment decision you regret? What led to them and how did they affect your process going forward?

My best investment to date has been investing in the CrowdStrike IPO a few years ago. A decision I regret is investing in the cannabis space before regulation becomes more clear. I assumed politicians were more rational and predictable than they turned out to be and my equity has been obliterated as a result. Luckily it is a tiny piece, but still, a lesson learned. Investment cases shouldn’t need a piece of legislation to pass to work. Aside from that, trusting management teams a bit more than I should have is something I’ve had to learn to avoid. I trusted some leaders pounding their chests on “macro immunity” throughout 2021 while their models were intimately tied to those macro cycles. They were wrong. I was wrong to believe them and should have trusted my background, experience, and education more than I did.

What are some of your favorite ideas on your radar now? (Long/short companies or industries)

]]>This week’s guest is Gautam Baid, Founder and Managing Partner at Stellar Wealth Partners and the author of The Joys of Compounding. Gautam is an avid reader with interests in a variety of fields.

You can follow his thoughts or connect with him on Twitter.

Hi Gautam, thank you for taking the time to do this interview. Excited to have you here! Can you please tell our readers a little more about your background?

I am the youngest of four siblings in my family and my parents, my two elder sisters, and my elder brother reside in Kolkata, India. Prior to my relocation to the US in 2015, I served for seven years at the Mumbai, London, and Hong Kong offices of Citigroup and Deutsche Bank as Senior Analyst in their healthcare investment banking teams.

As is typically the starting story of many investors, I got lured into the stock market out of greed during the final euphoric phases of a bull market. In this case, it was the 2003-2007 one in India. I invested in Reliance Power Sector Mutual Fund in late 2007 and Ispat Steel in January 2008 as both were in “hot sectors” of the times and both had recently appreciated “sharply in a very short span of time” when I had first noticed them.

So, I just engaged in the blind extrapolation of their recent price trends without paying any attention to their valuations. Recency and vividness biases are very powerful but highly costly behavioral mistakes. Both investments crashed 70%-80% within 12-18 months of my purchase. I had successfully gained admission into the stock markets by paying my tuition fees.

Despite this bad initial experience, my curiosity and interest in the stock markets always remained very high throughout the years of my investment banking career. We have just this one life to live our dreams and I did not want to waste any further time doing something that I was not passionate about.

I was so keen for a career shift that I relocated to the US (one of my relatives who is an American citizen sponsored my green card) without any job in hand! I thought I would land a job in my desired profile within a short time since I was a CFA Charter holder and this particular degree is generally considered highly valued in the investment management industry.

Alas, life is not a bed of roses for those trying to carve their own destiny. I got rejected in my first three stock market job interviews, but I did not give up. I was adamant that I am not going to go back to my previous field of work where the presence of perverse incentives constantly led to incentive-caused bias and conflicts of interest and did not suit my personal nature, so I kept declining all investment banking job interviews calls that came my way (even though they would have had very high dollar salaries).

At the same time, I ran out of whatever little money I had brought with me from India and to take care of my living expenses in the US, I did not want to sell even a single share from my portfolio of Indian stocks as I did not want to interrupt the process of compounding. So, I took up a minimum wage job as a front desk clerk at a hotel in San Francisco where I used to work during the “graveyard shift” (for the uninitiated, this is the shift that runs from 11 pm at night to 7 am in the morning).

Even though it was a big struggle for me physically, emotionally, culturally, and intellectually, today, in hindsight, I highly value those days of my life because, for the first time since the beginning of my professional career, I got some free time for myself to read and learn. This was the phase during which my learning curve really took off from a tiny base.

Little did I realize at the time that I was laying down the strong building blocks for compounding in my life. The pace of work from late night to early morning at the hotel was pretty slow and I made full use of the free time to read every single article published on blogs like Safal Niveshak, Fundoo Professor, JanavWordpress, Base Hit Investing, and Microcap Club among others. The passionate pursuit of lifelong learning had begun.

All of us who discover our calling in life get to do so through a defining moment, event, or experience. Let me share mine with you.

During a stormy night in San Francisco in mid-2016, I was at home (I used to rent and live in a single room as a paying guest. I was trying to save every single dime that I could during this phase) reading the 2012 edition of Tap Dancing to Work, a compilation of articles on Warren Buffett published by Fortune between 1966 and 2012. Immediately after finishing the book, I came to know that there was a more recent 2013 edition of it which contained one additional chapter.

I did not want to spend money on buying the newer version of the book, so I went to the local bus stand, got badly drenched (even while using an umbrella) while waiting for over an hour in the midst of the storm, and traveled all the way to a distant Barnes and Noble bookstore to read the final chapter of the book inside the store and save a few dollars (I had a monthly bus pass at the time, so the bus ride did not cost me anything).

That night I realized that I had finally discovered my calling in life. It is difficult to express in words the sheer intensity of the emotions, thrill, joy, and excitement that I experienced. I could not sleep that entire night. Only the fortunate few who discover their true passion in life will be able to relate to what I am trying to convey.

Luck, chance, serendipity, and randomness have always played a big role in various aspects of my life to date. One fine night in November 2016 while working at the hotel, I randomly clicked on the “quick-apply” button on a LinkedIn job application during my routine online job search.

I unexpectedly received an interview call for the job and that too for a senior role in an investment firm even though I had zero formal work experience in the stock market! And this was the phase in my life during which I was about to experience the power of compounding knowledge in action.

All those hundreds of hours I had spent during the previous year at the hotel reading the blog articles had built a strong intellectual foundation for me in investing (this is what I was lacking during my first three stock market job interviews in the US) and I excelled in all the three rounds of my job interview (body language derives from self-confidence and self-confidence, in turn, derives from knowledge).

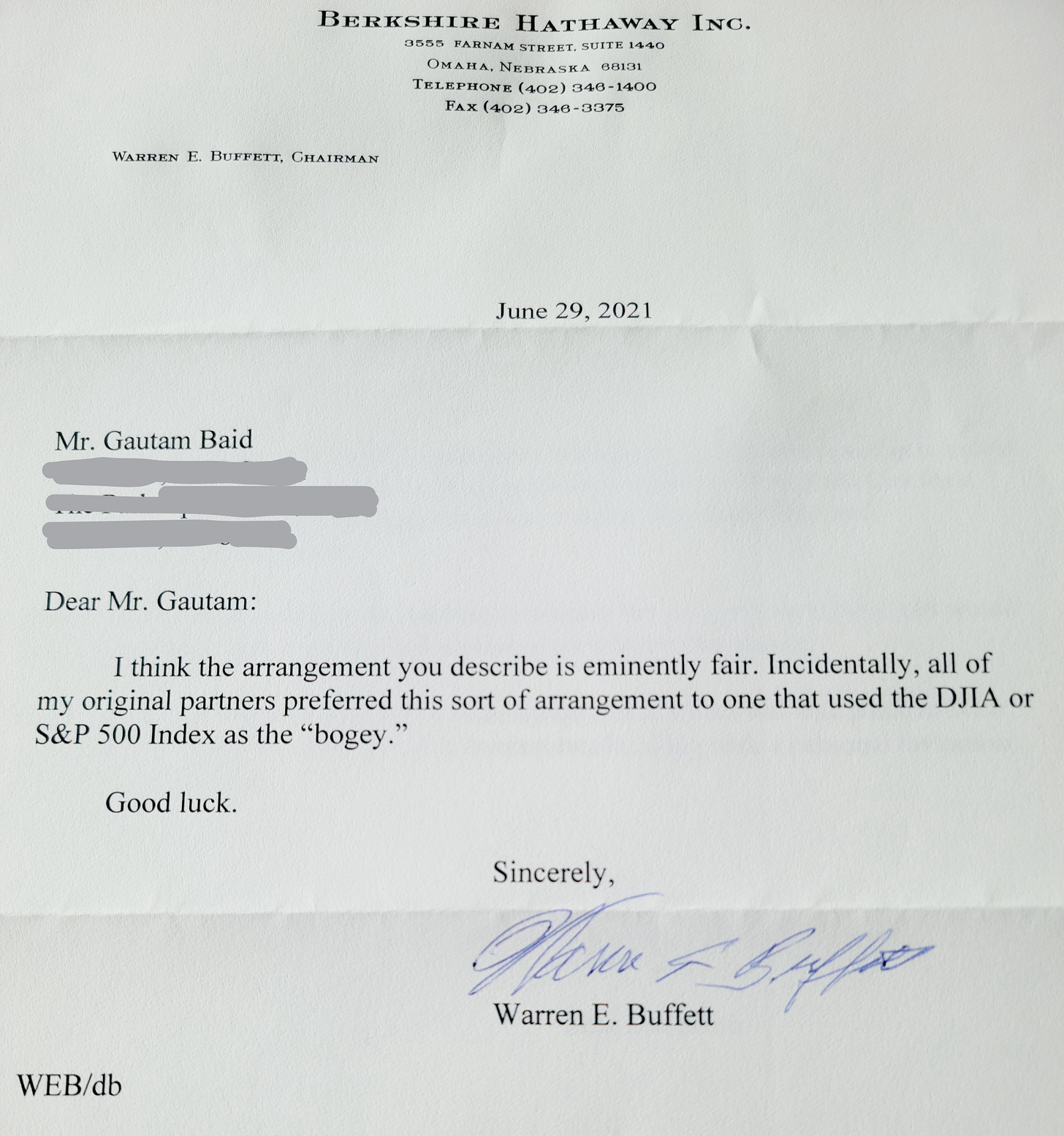

I was offered the role of Portfolio Manager of Global Equity Strategy and it was a dream come true for me. During my stint of 4.5 years at Summit Global Investments when I was tracking global markets, India clearly stood out to me with regards to the many high-growth investment opportunities in its stock market. In July 2021, I left my job to set up my India Fund in the US – Stellar Wealth Partners India Fund – to bring the India opportunity to investors in the US. The Fund went live in October 2022. Earlier this year, I also launched Stellar Wealth PMS for NRIs and Indian citizens. Both the India Fund and the PMS are modeled after the Buffett Partnership fee structure and invest in listed equities in India with a long-term, fundamental, and value-oriented approach.

Incredible. Congratulations on your success. How has your investment philosophy evolved over the years?

My personal investment philosophy has evolved over the years with time and experience in the markets. Initially, it was restricted only to secular growth stocks at reasonable to slightly expensive valuations.

But now, it covers multiple areas of the investment universe like spinoffs, merger arbitrage, cyclicals, deep value, and management change special situations. In a nutshell, I now invest wherever I find “mispricing” of value and a highly favorable risk-return trade-off.

Another key area of my evolution as an investor has been in the understanding of human nature and the significant role of incentives in governing individual behavior. Always think about the possible incentives involved in any situation before making your final decision.

What’s your research process like? What are some of the common red flags and positive signs when researching a company?

Between low-quality businesses at a cheap valuation and high-quality businesses at a fair valuation, my preference is always for the latter since I can have meaningful allocations of my portfolio in them with peace of mind and higher stress-adjusted returns. High-quality businesses typically demonstrate sustainable competitive advantages, known in investing parlance as “moats”.

Strong brands with “share of mind” which confer pricing power, network effects, high switching costs, a collection of patents (as opposed to relying on only one or two), favorable access to a strategic raw material resource or proprietary technology, and government regulation which prevents easy entry – these can confer a strong competitive advantage which in turn enables excess returns on invested capital over the cost of capital for long periods of time (also known as the Competitive Advantage Period/CAP).

Growing firms with high Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), opportunities for reinvestment at those high ROICs, and longer CAPs are more valuable in terms of net present value.

One of the most highly underappreciated sources of sustainable and difficult-to-replicate competitive advantage is “culture”, best epitomized by companies like Berkshire Hathaway, Amazon, Costco, Piramal Enterprises, and HDFC Bank, to name a few.

To illustrate the critical importance of culture just consider this: From 1957 to 1969, Warren Buffett did not mention the word “culture” even once in his annual letters. Since 1970, he has mentioned the word more than thirty times.

Some of my favorite books on competitive advantage are The Little Book That Builds Wealth by Pat Dorsey, Understanding Michael Porter by Joan Magretta, and Different by Youngme Moon. For learning about how to evaluate the culture of an organization, I recommend reading A Bank for the Buck: The Story of HDFC Bank by Tamal Bandopadhaya, both the editions of Intelligent Fanatics by Sean Iddings and Ian Cassell, and Investing Between the Lines by L.J. Rittenhouse.

Moving on, what has been the most important investing lesson you have learned from your time in the market?

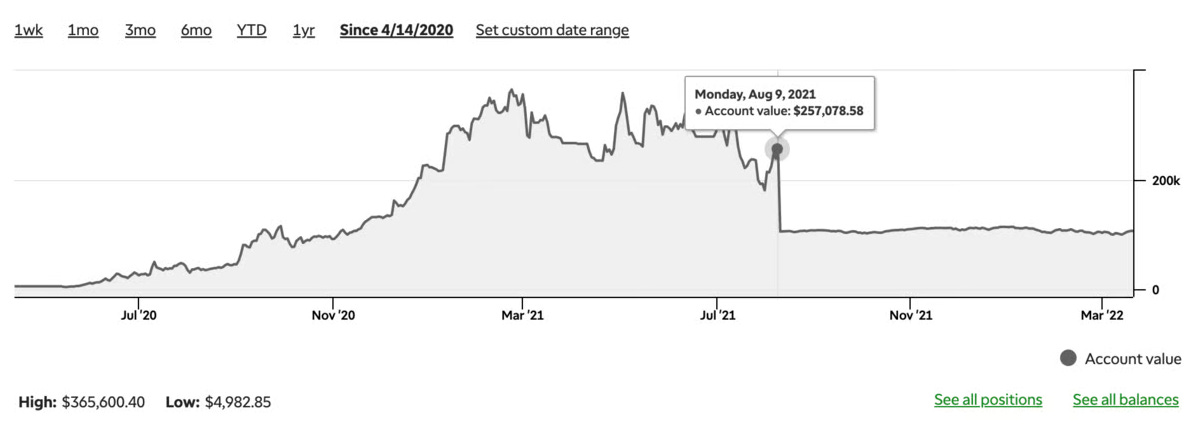

The answer lies in your question itself. It is “time in the market” and not timing the market that drives wealth creation. If I had gotten scared and exited the market during the periodic phases in 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2020 when my portfolio value fell 30%-35% (with many individual stocks down 40%-50%), then I would have completely missed out on the big bull market years of 2014, 2017, and 2020 which helped me achieve financial independence early in life. The words of Peter Lynch on this subject are noteworthy:

“Whatever methods you use to pick stocks, your success will depend on your ability to ignore the worries of the world long enough to allow your stocks to succeed. No matter how intelligent you are, it isn’t the head but the stomach that will determine your fate.”

What are some of your favorite ideas on your radar now (Long/short companies and industries)?

]]>This week’s guest is Matthew Tuttle, CEO & CIO at Tuttle Capital Management. Matthew has been managing money since the mid-80s and now oversees 8 different ETFs with $350M+ in AUM. Tuttle is famous for going against trends and was successful with his anti-ARK ETF returning 100% in just 5 months. He is hoping to replicate these results with the recent launch of the Inverse Cramer ETF.

You can follow his thoughts or connect with him on Twitter.

Hi Matthew, thank you for taking the time to do this interview. Excited to have you here! Can you please tell our readers a little more about your background and also about your investment firm Tuttle Capital?

I've been managing my own money since the mid-80s. I started on Wall Street in 1991 and worked for a bunch of different brokerage firms, insurance companies, and in 2003, ended up forming my own wealth management firm.

In 2012, other wealth managers started asking us if we could manage money for them and we formed a money management firm. Finally, in 2015 we started launching ETFs and have been doing that pretty much ever since. Right now we manage about $350 million in eight ETFs and got a bunch of other things we're planning on launching over the next couple of months.

Great. Out of the eight ETFs, we could see that you completely manage four of them and the other four, you partially manage. How does that work?

One of the things we do is to help other people who have great ideas launch ETFs. There are 5 that we are helping out on and in 4 of them, I am the sub-advisor.

We're always looking to partner with other investment managers who have interesting ideas. So we have always got a bunch of that stuff on the drawing board.

Something we are always curious about while interviewing fund managers is how much of their own portfolio is with their fund.

I've been trading since the mid-80s and I spend a lot of time trading my own account. I have got probably 10% of my portfolio on SJIM, which is our inverse Jim Cramer ETF, and the rest of the portfolio I actively trade.

Right now, I am sitting on a lot of cash and some small positions. What I've been doing lately is buying gold miners, shorting REITs, and shorting regional banks. We launched SARK, which is the inverse Cathy Wood (ARK), which we're not involved with anymore, but I actively trade in and out of that.

Overall, I would say that I have around 10-20% of my portfolio in our ETFs, and the rest I actively trade.

Got it. So what’s your investment strategy in a nutshell?

It very much depends on the environment — I'm more comfortable as a short-term investor. But you know, if we get a period where the markets are ramping up, I just buy stuff and sit on it.

Right now I am a short-term investor. I prefer counter-trend types of methodologies of buying weakness and selling strength. But again, if we get into a trending market, I will go back to being a trend follower. It just really depends on what's going on in the marketplace.

Does that mean that almost all of your portfolio is composed of individual positions?

Yes. It's all individual positions. I just sold all my gold miners recently because I didn't think that they should be going up that much. The only thing I had is I've got a bunch of puts on some regional banks and some REITs. I am long few companies. Overall, I've got about 12 positions right now.

Can we discuss a bit about how you finally came to this strategy? You have been investing for 30 to 40 years — how did it change over time?

The strategy has obviously changed a lot over time. When I started out in the 80s, companies were getting taken over. Then the strategy was pretty simple — You hear a rumor, and you know, you buy it, and then you wake up the next morning and find out it’s being taken over and it’s up 40%.

One of the best learning experiences I had was when that changed in the 90s. I was still trying to do what worked in the 80s and ended up losing a lot of money. My biggest loss was in 1991, when I was still trying to buy things on takeover, speculation, and the whole takeover boom was over. I then realized, alright, I gotta get smarter about what I'm doing. And from there, it's just been a constant and continual learning process.

What would you say are your top three long ideas or short ideas right now?

A quick note from MS — We first did the interview on April 12th and Matthew mentioned that he was still skeptical of regional banks and was short Metropolitan Bank ($MCB). As of today, the stock was down 20%! We reconnected with Matthew and here are his current positions.

I am still short a couple of regional banks, but I think the easy money is now over and you have to be very cautious on these trades.

]]>Welcome to investor interview #7. I’m putting together this series to bring you diverse experiences and perspectives from other investors.

This week’s guest is James Bulltard. James has vast experience building tools to study options trades and selling puts using the strategies he develops. He writes “The Running of the Bulltards” on Substack where he shares his insights and data. You can follow his thoughts here and connect with him on Twitter as well.

We got to ask him about:

His journey in the options trading world and performance

How he shares his insights and picks

Why options flow is important, even for fundamental/long-term investors

How he allocates his portfolio

Why he disagrees that price action is based on fundamentals

Also, for premium subscribers:

What are James’ favorite ideas and themes on the radar right now?

What can fundamental investors learn from technical analysis?

What does his research process look like?

What red flags does he look for in a company?

Subscribe here for full access to all paid posts and investor interviews:

Hi James, great to have you with us. I discovered you through this Twitter thread where you share your journey and performance. Can you please tell our readers a little more about your background and also about what you do?

I worked as a trader at a vol firm in Chicago right out of school, and spent years working in various roles in New York and Miami afterward. Afterward, I ended up managing a family office for a previous client of a firm I worked for. I did that up until my retirement in 2022 to spend more time at home with the birth of our second kid.

I wrote that thread you are referencing in March after 9 months of publishing all my work on my substack. When you post things online, it’s hard for people to believe you until you show them. That thread has all 9 months of my postings where I outperformed the S&P by 90% in a fairly horrible market. For me, it all began in June 2022, when I saw one of the oddest options trades I’ve ever seen be placed. I began writing on Substack that day because I couldn’t rant on Twitter with character limits and it just took off when Sierra Wireless was acquired a couple of weeks later. That trade I noted was the first in a series of giving people insights into the real inner workings of the market. My Substack has turned into one of the fastest growing ones on their platform: my objective is to take the millions of options placed daily, sort them into a curated list of the most unusual ones every day, and input them into my database to model trends in the hopes of finding a direction to trade.

Is there a place where you share your picks publicly?

I do not make “picks” but I do post my open book every day on my Substack just in an effort to be open and transparent about what I’m doing for those who care, but the reality is that most are on my Substack for a cheap way to obtain institutional data. Retail investors typically aren’t going to pay $2,000/mo for a Bloomberg Terminal to have access to a platform where you can gather data. I took a problem I saw in that all the existing platforms that offer options data offer too much and most of it is not important. I try to cut out the noise and share the best data for a low fee. For me, I do this work anyways for my own daily homework to see what tomorrow’s game plan is. I’m just publishing it now for others who want the same data for their own discovery process.

Why are the options flows important?

They’re giving a live look at huge bets institutions place. I know long-term investors like looking at 13fs to see who is doing what, but that is backward-looking data. By the time investors see it, the funds have already made a fortune – but the options market is live. I’ve called out so many moves in advance whether it be Pinterest before the massive Elliott Management stake was disclosed or even that recent 30% move in Alibaba. The option flows show what the big funds are doing and when you see one ticker attacked over and over, you can tell something is brewing, the what isn’t my concern.

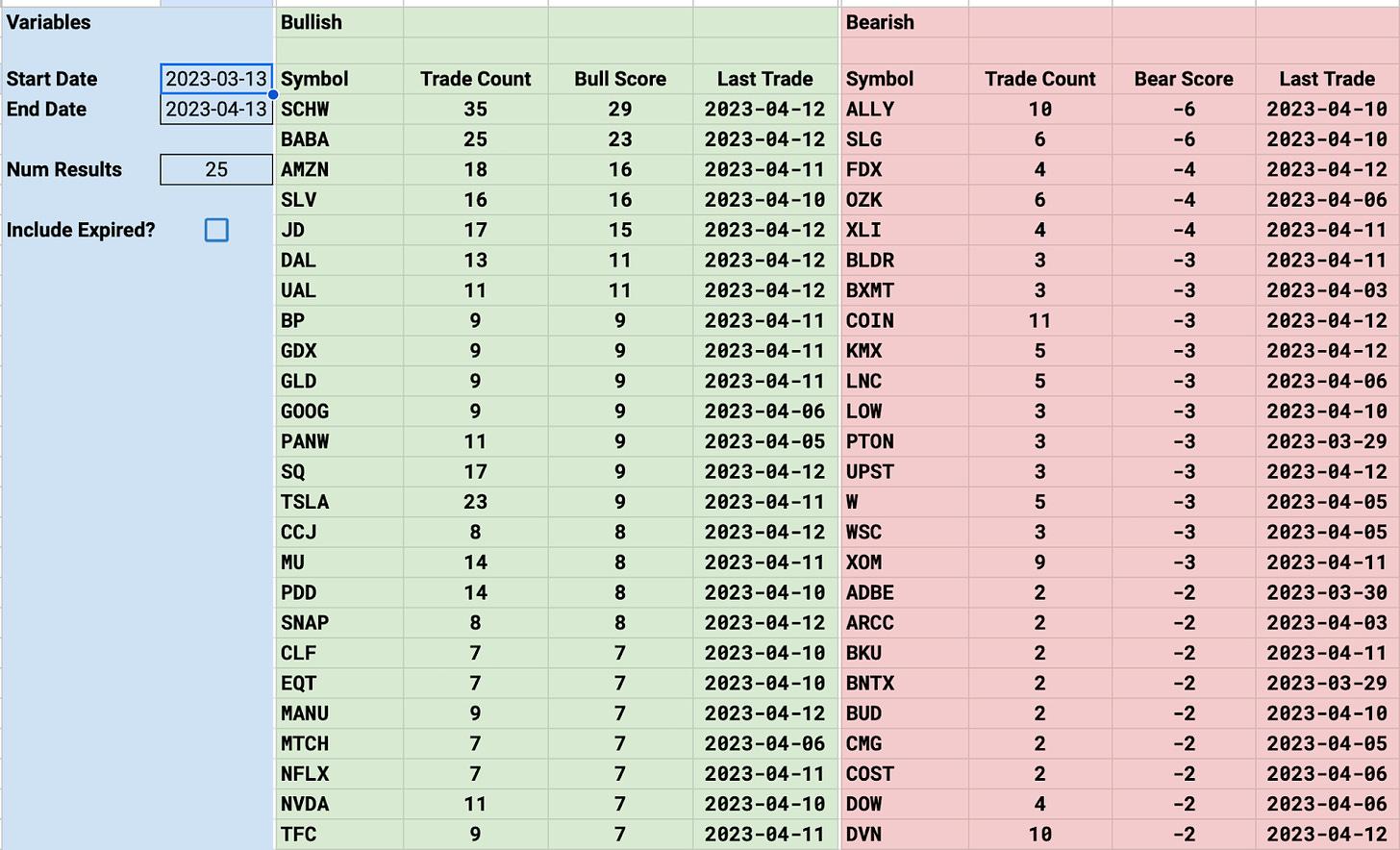

Having my custom database allows me to share with readers every day not only a list of the day odd action, but also share trends over multiple timeframes ie weeks, months,etc. Something like this is simply just taking all the unusual trades I input into my database to give me a bull/bear score which is just a net of all the trades. This gives me an idea of pockets of emerging strength which allows me as a trader to attack areas of strength as they are gaining steam. What you can see below is a screenshot I took of the trends I am seeing over the past month (the timeframe is on the left). You can see the total amount of unusual action I’ve noted and the net of them. I don’t know anyone who uses anything like this – it is all my own modeling after years of working with this data and wanting something customized for my own needs:

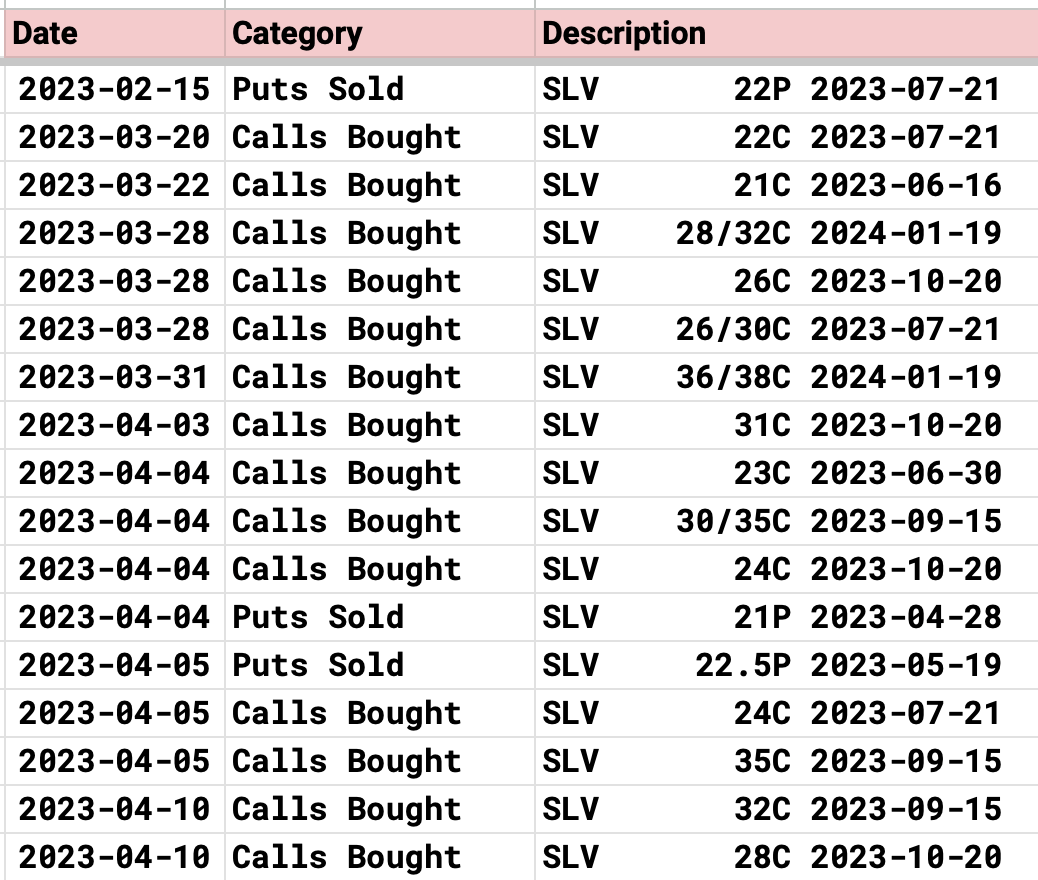

As you can see above something like SLV has been trending hard for the past month, and if you look Silver has had quite a run, I can then search my database ticker by ticker to see all the trades that my parameters caught and for SLV this is what it shows. This allows me to see pockets of demand for the equity from institutions, and it helps guide me in my decision-making in terms of what levels I want to sell puts at.

That’s an interesting strategy. How much of your portfolio do you use for this? Do you have any exposure to passive index funds? Something we are always curious about while interviewing fund managers is how much of their own portfolio is with their fund.

When I retired, obviously protecting my assets was the number one objective. I am younger so I have a long time to go. Obviously, I could go back to work whenever, but that isn’t the goal – so the first thing I did was to invest the bulk of my capital into some NNN properties. I wanted a really hands-free experience, I know lots of investors prefer single-family or multifamily, but NNN offers lower returns in return for longer-term corporate-backed leases and a mostly hands-off experience. I would say probably 60% of my portfolio is commercial real estate. I would say another 30% is in various equities and private investments, I do not own any passive funds, and lastly, 10% or so is in my trading book that I focus on every day.

What made you get into investing and what’s your investment strategy? Which industry do you focus on? Would you consider yourself a long-term or short-term investor?

I got into investing at maybe 14 years old. I had an older cousin who was my big brother so to speak, he was a stockbroker back in those days and he would always work with me when he was in town visiting. He helped me buy my first stocks. He helped me learn a lot about the market. I was always fascinated with his nice cars and as a little boy who loved cars, I wanted to do whatever it took to get something like that so I listened intently to everything he would teach me.

What’s my investment strategy? If I had to explain it, I would say it is basically taking all the available data known to investors using options flow, along with technical analysis to model direction, and then selling puts into strength in an effort to generate income. That sounds like a lot but I sell puts because I always want to enter equities lower. Why would you pay full price ever for a stock? Even Warren Buffett sells puts to enter trades. The way I model data is simply an effort to find equities that institutions are buying and then selling puts lower, to try and ride the wave so to speak.

“Fundamentals drive stock prices, that couldn't be further from the truth, what drives stock prices is simply, is someone buying it.” – Can you explain this further? Also, if this was the case, why is someone like Warren Buffett extremely successful while we don’t have any comparable in the day trading world?

As for the second part, there are many comparables in the trading world that blow away Warren Buffett, I wouldn’t call it the “day trading world”. Look at guys like Jim Simons, Ken Griffin, Steven Cohen, and many more. Their returns are amazing but Buffett has definitely done it for longer so he is more prominent. But there are plenty more active managers who have significantly higher returns, though not everyone has access to capital like Warren Buffett.

What drives a stock price is the amount of buying going on, that’s it. Look at something like NVDA – fundamentally it doesn’t make sense and a lot of short sellers have learned a hard lesson this year trying to use fundamentals to justify their trade. Stocks don’t have to make sense short term, if they did, we would have an efficient market, but we don’t. We have a market driven by trends in the short term. If the fundamentals of the company you’re looking at are as good as you think they are, these funds and their armies of number crunchers will have established a position long before retail at home is all I’m saying. In the end, these funds and their positioning are what drive markets and my objective is trying to align my positioning with them.

What are some of your favorite ideas on your radar now? (Long/short companies or industries)

As a trader, that isn’t something I think about. Trends are constantly changing and new sectors of strength are always emerging. There is always a bull market somewhere and my focus is on finding and utilizing all the data that is out there. In terms of my long-term investments and the themes I’m interested in…

]]>This week’s guest is Marco Pabst, Group Chief Investment Officer at Arbion. Marco has more than 30 years of experience in investing and his team currently manages several billion dollars across equities, fixed income, hedge funds, and private investments. You can follow his thoughts or connect with him on Twitter or Linkedin.

Hi Marco, thank you for taking the time to do this interview. Excited to have you here! Can you please tell our readers a little more about your background and also about your investment firm Arbion?

I started as an equity research analyst on the sell-side, working for a large German private bank covering small and midcaps, and then focused on European software companies, working for UBS in the late 1990s. After the dot-com bubble, I moved to the “buy-side” and joined a multi-family office in London in 2004.

We subsequently grew this business to just under $5bn and then sold it to Swiss private bank UBP - Union Bancaire Privee - in 2018. UBP currently manages around CHF 140bn ($156bn) globally for wealthy clients.

However, over time I felt that our clients preferred working under a multi-family office setup and, therefore, I left the bank last year, having been their CIO in London and Chairman of the global equity committee of the bank.

At Arbion with a team of 30, we manage several billion dollars across equities, fixed income, hedge funds, and private investments for around 200 families worldwide. On the liquid side, our core business is discretionary multi-asset portfolios but we also run tailored fixed-income and equity allocations for clients. In terms of structures, we typically run managed accounts but we also have a range of funds.

Incredible. Congratulations on your success. Something we are always curious about while interviewing fund managers is how much of their own portfolio is with their fund.

As I run or oversee most of Arbion’s strategies, logically all my liquid funds are in investments that we also own for clients. If I identify what I believe could be an interesting idea for clients, why would I not also invest my own money into it? So, yes, all my skin is in the game.

That’s nice. What made you get into investing and what’s your investment strategy?

As a student, I started trading stocks and warrants of Japanese companies at the tail end of the Japanese equity bubble in the early 1990s as they tended to be mispriced, trading in Europe versus their home market. I then focused on European deep-value names before moving into what we call growth stocks today. Alongside that, in macro terms, I was in the market during the 1994 bond crash, LTCM, the Russian, the Asian crisis, and everything that followed.

So whilst my primary interest is in equities and credit, I also spend a fair amount of time looking at the bigger picture. This blend of macro and micro is what I find the most interesting, where everything comes together, not always but most of the time. As most people just focus on one particular area, they often ignore signals from others. Ignorance is every investor’s worst enemy.

Leaving the macro part aside, and whilst I don’t mind the occasional trade, I would consider myself a medium to long-term investor. If I can find the right business to invest in, ideally I would like to own it for as long as possible.

Given the number of market crashes and hype bubbles that you have experienced, what has been your best learning? Can you tell us a bit about how your mindset toward money and investing changed over the years?

There are many things that I have learned over time, and almost all of them are associated with mistakes I made. This led to an investment process that has elements of risk management at every single step even if it is not explicitly called risk management.

As a result of this negative selection process, there are many areas and strategies that I don’t spend much time on anymore, as the odds of success in them, at least from my perspective, are stacked against me.

I tend to ignore most things that are exotic, illiquid, looking too cheap, or overly complex. Similarly, I would not spend much time on industries that are highly commoditized, very complex to evaluate, extremely capital-intensive, have no particular edge, or have not shown any attractive sector economics historically. Typically, this includes mining, airlines, football clubs, biotech, most oil companies, banks, and some others.

This has narrowed my focus towards companies with defendable strong business models, that are not too cyclical, generate high returns on capital, are run by strong and incentivized management, and are not overly leveraged. Therefore, stable non-cyclical compounders are the ideal bedrock for a great long-term portfolio. Whatever the macro worry might be, the best names also tend to bounce back the fastest.

This led to another important learning which is that time in the market is much more important than trying to time the market, which is what many people appear to be attempting primarily. However, I would be lying if I said we don’t also look at timing aspects. There are pros and cons to it but I admit, that less is more sometimes.

I strongly believe that there is no growth without value and no value without growth. When I look at many companies today, including large tech businesses, I would find it hard to categorize them - hence I tend to skip this whole debate.

I believe most people who own stocks today are not very familiar with them. I am convinced that the average investor spends more time choosing a $3,000 TV set than a $50,000 stock investment. Hence, I am convinced that someone who reads the company presentation from the investor relations section is already ahead of 75% of his co-investors in that company. Annual and quarterly reports contain a lot of interesting details that help build a good mental picture of the business in question and this accumulated knowledge then leads to a much steadier hand, holding this investment hopefully for the long term. From that base of knowledge, it is then easy to expand into the broader sector and other competitors. As a result, the time I spend reading it is increasing every month.

Yes. We have also observed this time and again where investors go all in without doing adequate due diligence. Historian Cyril Parkinson coined a thing called Parkinson’s Law of Triviality that fits here perfectly. It states: “The amount of attention a problem gets is the inverse of its importance.”

So, what’s your research process like? What are some of the common red flags and positive signs when researching a company?

The size and scope of our investment universe have not massively changed over the years. There are just not that many good companies out there that are worth considering for investment. Hence, the process is more gradual now as we keep processing new information to inform an existing view.

The fundamental selection process is fairly straightforward and not too unique: we look for not-too-cyclical businesses with high and sustainable returns on investment and a strong position in their core markets. In addition, management and balance sheet quality are also important. I am not a fan of too much leverage, i.e. anything higher than 3x EBITDA typically. So far so good.

What I then like to do is to look at the whole capital structure and see if there is any other interesting angle. For instance, in some cases, I start investing via selling out-of-the-money put options because implied volatility was temporarily very high for the stock for some reason. In several cases, this is how an investment started – with a short put that typically yielded more than 20-25% annualized.

Sometimes, we also approach an investment from the bond side only. Spreads could be attractive for some reason or occasionally we also find the odd busted convertible that pays an interesting yield and has the call option upside. As always, there are many ways to skin a cat.

Looking at the whole capital structure is obviously generally quite informative as it reveals what other markets are thinking about a company. Very often, one can find cases where the stock price is under pressure but credit is trading fine – a clear divergence. Conversely, a weak picture on the credit side but unfazed equity would be a major red flag in my books.

Aggressive accounting or accounting changes in that direction are also always a precursor for exiting a position. Frequent management changes are another.

On the other hand, insider purchases are certainly a positive as are conservative accounting methods and incentivized management. A strong R&D profile in businesses where this is important, strong cash conversion, and sector leadership are also key elements we are looking at.

Once we have identified our target investments, I like adding a somewhat contrarian angle to it and maybe this is where an element of market timing is entering the equation too. I like entering such positions when they are somewhat out of favor (after a profit warning or another otherwise short-term issue). Equally, I am rather a seller when something is in unusually high demand. This general approach is not limited to stocks.

A good example was Brexit Day – the day after the 23rd June 2016 Brexit referendum. The result of the vote was unexpected and domestic equities crashed alongside the currency. We were heavy buyers of these names on that day and the day after when many of them lost 30% and more during the panic selling. Buying when others were indiscriminately selling for little fundamental reason turned out to be an exceptionally profitable opportunity for us.

Two other more recent examples maybe to highlight this approach outside direct equities: In the third quarter of 2019, equity markets were riding high whilst the yield curve was inverting, signaling some potential trouble ahead. Because of the bullish equity environment, implied volatility was low, so I hedged the majority of our equity holdings at little running cost. The insurance premium simply was so low that it almost didn’t matter, creating a very asymmetric potential return outcome. Then, as the COVID pandemic broke out, we were almost fully hedged and performance benefitted accordingly.

Another important allocation decision and similarly contrarian was when I drastically reduced fixed-income holdings in the course of 2021. Yields at the time were still very low but started rising and the risk of increasing inflation and more hawkish central banks was on the horizon. This simply created an environment for investment-grade bonds where there was little upside and a lot of downside. The rest is history. After the bond crash of last year, we have built back a lot of exposure in the space as the risk/reward has completely changed: bonds are now a very viable alternative for investors vis-a-vis equities and they also have a hedging value again - providing protection when risk markets decline.

There is a lot of research on how index funds are beating active fund managers – Where do you think the need for active management arises? How do you think the fee compression affects the asset management landscape long-term?

I believe active management still plays a very important role in asset allocation, i.e. deciding what areas in the market a client should be focusing on and developing appropriate strategies for it. Risk management is also critical in that context, i.e. managing net exposures in equities, managing duration, and credit risk within fixed income as well as currency overlays.

Passive strategies and index funds play an important role in our portfolios, especially in equities, when we are just looking for ways to get liquid exposure to broader sectors or geographies without trying to pick the best companies.

Within fixed income though there is still tremendous value in active strategies and “bond-picking” as indices are almost always tilted to the fundamentally worst, i.e. most-indebted, issuers. Here, one can add substantial value for clients. Also, in contrast to funds/ETFs where one is typically exposed to more or less constant duration, I can easily design fixed maturity portfolios that match a certain event in the future and run down into cash over time.

Fee compression has been an issue across the board, from ETFs to hedge funds with discretionary strategies sitting somewhere in the middle. I believe this trend is unlikely to stop anytime soon although we are approaching some kind of floor, certainly for the more active strategies.

There simply is a certain cost associated with a very tailored strategy that requires constant attention by professionals and this needs to be reflected in a fair price. At current levels, I don’t think that the price is very high. For commoditized strategies which can effectively be run by a machine, costs will continue to be kept under pressure by competition.

More generally speaking, the broader answer is of course, that a larger scale is required. The threshold to operate a financially sustainable business in terms of minimum AUM today is several times higher than what it was 20 years ago.

Interesting. So, what are some of your favorite ideas on your radar now? (Long/short companies and industries)

More thematically, the areas I spend a lot of time on now are:

]]>If you’re new here, you can subscribe by tapping this button for content that will make you a smarter investor.

Of Dollars and Data is a great example of how you can always go deeper into financial topics with a consistent vision without caving to the pressure of novelty. Nick Maggiulli writes about how even God can’t beat Dollar Cost Averaging, Portfolio allocation, how investors should think about money, what risk isn’t, and his trademark idea to “Just Keep Buying” in great detail and from different angles.

Nick has built a voice with his writing that people trust and look to, not only to understand what is going on in the market but also to think and rethink their own relationship with money. One of the reasons is that his articles are based on solid data and historical research, and he does not make claims that he can’t back up. But the more important aspect is the human connection because of his personal stories that illustrate how his thinking about money has changed with time.

Let’s dive into the interview to unpack his approach toward money. In this issue, we cover:

Why you should optimize your income over investments at the beginning.

Why people try to beat the market with statistically impossible strategies.

When and how to select a financial advisor.

How to filter out noise and fake news related to investing.

Which is more important: Asset allocation or asset selection?

Why maxing out your 401k is over-rated – and what the most under-rated investing advice is.

Let’s get started.

Personal Journey

MS: Can you tell me a bit about your personal journey in life and investing? How have your thoughts about money and investing changed over the years?

Growing up, my parents didn’t have much money. Though I never went hungry, I also knew that there was much to go around. As a result of this, my early mindset around money was one of scarcity. Even through college I only ordered off the dollar menu at a fast food restaurant, though I could afford pricier items.

Over time though, this changed. I learned more about personal finance and investing in college and in the years after. As a result, I began to see money as a tool we could use to change our lives. Today I think investing is incredibly important, but its importance becomes more amplified as you have more money (typically later in life). For most people, their career and their income will be the dominant factor in their early financial success, so I try to get people to focus on that more instead of worrying too much about their investments.

MS: Unlike the usual brand of financial content which is very anecdotal, you have a focus on historical analysis and using data to back up your arguments. You have developed your own niche as a result. What motivated you to start writing about investing and how was your approach shaped?

I’ve always had a passion for investing and I also enjoy programming/data science. I saw a potential fit between the two and thought it would be fun to start writing about finance and economics for fun. I eventually found my niche in the investment space and haven’t looked back.

My approach was shaped by questioning a lot of what we hear (which usually isn’t backed by data). So I simply ask: Is that true? Then go about trying to find out. Many times this leads to nowhere, but once in a while I find a surprising conclusion.

(MS: One great example of testing assumptions to find the truth – Should you invest in stocks lump-sum or DCA? What about other assets like Bitcoin? This article covers it all.)

MS: Who are some financial writers who have had an influence on your style?

Early on it was William Bernstein and Jason Zweig, but over the years I’ve become far more influenced by Morgan Housel. Bernstein taught me the importance of analytics and Zweig the importance of human psychology, but Housel taught me the importance of storytelling. As much as analytics matter, we are still humans at the end of the day. And humans are captivated by stories. So if you want your message to spread into the world, you need a good story.

Investor psychology

MS: Your book “Just Keep Buying” is a comprehensive take on all aspects of investing – From the basics of investing to retirement and tax planning. There are some consistent themes in both your book and your blog posts.

For example, you are a staunch advocate of investing in low-cost index funds for most individual investors, and you have written multiple articles about why timing the market and picking stocks are statistically impossible strategies. Why do investors still resort to these strategies? Is it greed? Is it a hope that “this time is different?”? Or do they assume that any chance however small is probably reserved for them?

I think the reason most people try to time the market is based on both fear and greed. Selling at the first sign of trouble is fear-based, while “buying the dip” is greed-based. There is no evidence that either strategy works consistently, but they do work at times. I think this distinction is important, because this is why people market time.

If I told you that no one could ever successfully call a top or bottom, I’d be lying. People have done this before and they will do it again. However, I don't think anyone can do this on a consistent basis. That’s where market timers fail. They may be right now, but they will be wrong later.

And in being wrong they could end up missing out on a lot. My favorite example of this was all the people who sold in March 2020 only to see the market hit new all-time highs in less than 6 months. Predicting the future is hard, which is why I don’t try to do it.

MS: I like the book’s emphasis on how fulfillment, not money, should be the thing to optimize for. Why is it so hard to make this switch for people on both ends of the spectrum (net savers and net spenders)? How can they design a place for investing in their life to optimize for fulfillment rather than investment returns?

I think people have to spend a lot of time analyzing their big decisions in life to figure out what is really motivating them. Once you know that, then you can ask yourself whether it makes sense to continue those behaviors.

For example, we always hear the cliche example of the successful person who works so much that they miss their children growing up. It starts with them skipping out on a sports game or a dance recital and never stops after that. My question is: why is that person working so much? The obvious answer is money, but given how successful they are, money probably isn’t the actual reason, it’s something else.

I think by digging deep inside yourself, you can go through the same exercise. Ask yourself why you do the things you do. Why do you work in the job you work? Why this field? Why did you choose this life partner? Etc. The goal is to know yourself and then solve life from there. That’s how you maximize fulfillment.

(MS: Check out Nick’s piece on Why you shouldn’t optimize your life.)

MS: The book provides many rules of thumb and heuristics that can be used right away, like the 2x rule. One trick I found very useful was how restricting choices artificially can actually result in more peace of mind:

“Holding US stocks for three decades is much harder emotionally than paying off a mortgage. When you have a home, you don’t get the price quoted to you daily, and you probably won’t ever see its value cut in half.”

– Nick Maggiulli

Environment design is seldom discussed when it comes to investing. How can investors design their environment to reduce stress in investing?

The best environmental design I know of is partial ignorance—don’t care too much. For example, though I write about money all the time, I rarely think about it in my personal life. I understand that this is a privileged thing to say, but I’m not even a millionaire. I’m just someone who is trying to enjoy life and helping people with their money along the way.

Investment advisors, asset allocation, and risk

MS: Your first article was about how hedge funds get rich where you discussed the role of fees, and how funds seldom beat the market. In such a world, what is the role of investment advisors and money managers? What should investors look for?

When it comes to hiring a wealth manager, you should focus on their approach to financial planning, how they make you feel, and their competence. These are all things that the wealth manager has full control of and things that you can easily analyze. No one can control what the market does, so find someone that adds value beyond the portfolio.

(MS: Read more at “When should you hire a financial advisor?”)

MS: Is asset allocation more important than asset selection? Why?

David Swensen, the late famed investment manager, once said that your portfolio returns come down to three things: asset allocation, market timing, and security selection. And, after reviewing the data, asset allocation represents about 90% of the variability in returns.

So, to answer your question, asset allocation is far more important than asset selection for the vast majority of people. Deciding what risk assets to own and in what proportions will have a bigger impact on your portfolio than just about anything else. Of course, this isn’t an easy task, which is why I tell people to focus on broad diversification no matter what they do.

MS: What are your thoughts on a barbell approach to investing?

I see why people like this approach, but I don’t favor it for behavioral reasons. The barbell approach has you holding lots of low-risk assets (i.e. cash) and lots of high-risk assets (i.e. crypto, single stocks, etc.) at the same time. Unfortunately, I think this approach leads to a higher probability of bad investor behavior when times get tough. I think 2022 is a great example of this where many high-risk assets are down 50% or more, while the overall market is only down 20%.

It’s not that the barbell approach couldn’t work, but I think many people would have a hard time sticking to it over long periods of time. Their higher chance of bailing when times get tough makes it a harder strategy to follow than my “Just Keep Buying” indexing approach.

MS: You have written about the existential risk in stock picking – That you can never know for sure whether you have mastered the skill or whether luck worked in your favor. Why is that important? Someone who thinks they can follow in the footsteps of their investing heroes (like Buffett or Lynch or (gulp) Sam Bankman-Fried) might think that they need to get it right only once. Is that a reasonable way to think about risk?

You don’t need to be right only once to be a great stock picker. You need to be right 6 out 10 times and you have to do that consistently over many decades to be the next Buffett, Lynch, etc.

But do you really need that level of returns to be financially successful? I don’t think so. Most people need far less to live an amazing life. Unless you are trying to be remembered as the next Buffett, there’s no point in trying to be like him (or anyone else).

Once again I would analyze the motivations behind why you want to be a stock picker and determine whether those motivations make sense.

Financial media and perception

MS: How do you think financial media and the abundance of investing resources have affected investor psychology? You have written about how anecdotal stories are sensationalized to grab eyeballs – Can you suggest a simple framework for investors to filter through the noise and assess the validity of financial news and stories in social media?

Ask yourself: is this going to matter 20 years from now? If the answer is no, then maybe you shouldn’t be paying attention to it. This is why I almost never follow macro and don’t think most people should either. It’s mostly wasted time and energy.

MS: The market has always been influenced by perception, but it looks like the last 2-3 years were dominated by perception-based assets. You have written several articles about crypto, the memestock phenomena, etc. as they were happening. Why are narrative-driven assets so hot all of a sudden, and will they become a mainstay?

There are basically two ways in which assets increase in value: fundamentals (increased earnings, value, etc.) and flows (people are bidding them up). You can make money following flows, but it is a difficult game to play especially over long periods of time.

It’s difficult to say which assets will become mainstays based on flows because preferences change over time. What’s hot now may fall out of favor and vice versa. It’s kind of like fashion or music popularity, it varies based on lots of things.

This is why I recommend investing most of your portfolio in income-producing assets. These assets should follow fundamentals in the long run so you can worry less about flows.

MS: A couple of questions from a devil’s advocate POV. Aren’t equities perception-based assets themselves?

Once a stock is out in the market, what tethers it to a company’s performance? Is it just the regulatory framework and institutional infrastructure?

Does that mean regulation can make crypto mainstream like equities?

Well, technically, every asset is based on what other people are willing to pay for it. So while this can vary from fundamentals (i.e earnings and earnings growth) in the short run, it should converge in the long run.

Regulation might make crypto more mainstream, but there will also need to be other use cases for it other than speculation.

MS: A lot of the debate around crypto has been the idea behind the asset. But are exchanges and the infrastructure the bottleneck that nobody is thinking about?

FTX and several other exchanges were not crypto themselves, they were the gateway to access the crypto world, and that was the weak link. When we do a historical analysis of equity markets, are we over-rating the robustness of the equity market infrastructure? They are only a few hundred years old after all.

Equity infrastructure had at least a few hundred years to evolve, which is a feature, not a bug. Crypto tried to go mainstream in 10 years without any such process and we are seeing the results of that today.

I find it ironic that the group of people who support a system based on not trusting others ended up putting so much trust into so few individuals. I never hold my crypto on an exchange and you shouldn’t either.

Personal experience and working with data

MS: Your article on viaticals blew my mind – arbitraging death to make money is the most metal idea in finance I’ve come across. Are there any other such wild strategies that people don’t know about?

There definitely are but access tends to be limited (based on bankroll). I also wouldn’t recommend any of these approaches for most retail investors as they may require more expertise. This could include things like litigation finance (financing lawsuits) and royalty investing.

MS: Your articles on your personal experiences and how they influenced your thinking about money and life are some of my favorites - For example, Regrets, It’s never too late to change, and Losing more than a bet.

Personal experience has a huge impact on how people think about money. Sometimes it can have the opposite effect, where people generalize unique cases they know about (like a successful entrepreneur or a lottery winner, without taking survivorship bias into account) and apply it to themselves. What’s a healthy way to incorporate personal experiences into the way you think about money and life, by placing them in the appropriate context?

Great question. I think the best way to incorporate personal experience without getting biased is to also consider what the data shows. I don’t think data is a silver bullet, but if your experience doesn’t fit the typical outcome then you might want to adjust your beliefs accordingly. Of course, there will always be exceptions to this, so use your judgment accordingly.

(MS: Check out Nick’s article on Why Personal Finance has become a bit too personal)

MS: Apart from backing your articles with historical data, you also open-source your analysis programs written in R and share the links. If someone wants to adopt a data-driven approach to testing their own ideas and assumptions as an individual investor, where can people start? Do you have any suggestions about the road to becoming a data-driven investor?

I think everyone should start where they are comfortable and work from there. If that means Excel, that’s fine. I suggest learning how to do financial math (I.e. How to move money through time, How to calculate drawdowns, etc.). There’s lots of value in understanding the basics very well because you can always fall back on them.

Closing thoughts

MS: What is one idea you discovered in the last few years that blew your mind and changed the way you think about something?

The book Die with Zero. Many of us are over-saving and we probably don’t realize it. Better to spend more of your money while you can then die the richest person in the graveyard. It completely changed how I viewed spending money and I would recommend it to anyone.

MS: What is the most over-rated idea in investing?

For those in the U.S., it’s maxing out their 401(k). Think there is far more to life than saving money in retirement and think the tax benefits aren’t as large as many believe. Of course I support saving for retirement, but I think there are probably too many people maxing that don’t need to be. (MS: Check out Nick’s article on Why you shouldn’t max out your 401k for a detailed explanation)

MS: What is the most underrated idea in investing?

Return on hassle. The basic idea is that higher returns aren’t always better if you have to spend more time/energy to get them. For example, there are a lot of real estate investors who have “passive” income that isn’t quite so passive. Dollars and cents matter, but HOW you earn those dollars and cents matter too.

MS: Is there a book, podcast, a blog, or anything else - that you would like to leave as a recommendation to readers?

Check out Money With Katie and Jack Raines. My two favorite relatively newer bloggers in the finance world.

MS: Do you have any idea or suggestion that our readers can take away to become more well-informed investors, or even make investing a little more enjoyable and stress-free?

I’d assume most of the people reading this are doing relatively well financially. Therefore, I think their problem won’t be growing their wealth over time, but how to spend their wealth to live a fulfilling life. This isn’t as easy as it sounds. You have to work at it actively.

So I’d recommend spending time on that. Be purposeful. Figure out what you really want. Life becomes much easier after that. Thank you for reading.

Thank you so much for reading and being a continued supporter of Market Sentiment! If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and tell a friend about us. You can even forward this paywalled content to a few friends for free :)

But first head over to Of Dollars and Data to read more of Nick’s writing, and check out his book “Just Keep Buying” on Amazon. It’s a great book to think about investing holistically, whether you are a beginner or a seasoned investor.

Were there any topics you wanted to know more about? Whom do you want me to interview next? Let me know in the comments!

Disclaimer: I am not a financial advisor. Please do your own research before investing.

All views are Nick Maggiulli’s alone and do not reflect the opinions of Ritholtz Wealth Management LLC and its affiliates.

If you’re new here, you can subscribe by tapping this button for content that will make you a smarter investor.

Announcement!

Before we jump in, I want to inform you that we are starting a custom portfolio review service. If you have been a long-time reader of Market Sentiment, you know how much importance we give to data analysis and backtesting. We have built an extensive set of tools over the past year to analyze and backtest various strategies.

Effective portfolio reviews can help you save hundreds of thousands of dollars over the course of your investment period by reducing the overall expense ratio, optimizing risk metrics, and diversifying your investments.

If you are interested, please fill out this form (heads up, we can only process limited requests (~100) and it would be based on first come first serve!)

Last week, we went through ’s (AKA Moontower Meta) journey from options trading to investing and his excellent set of tools and frameworks which you can start using right away to think probabilistically and make better decisions in investing and life.

But trading and investing are just one aspect of Kris’s writing - He is also passionate about learning and has created many excellent resources to help investors better their game. Whether you’re a beginner looking to get a solid footing or trying to broaden your horizon after years of investing, his resource lists are invaluable!

In part 2, we cover the challenges in educating yourself as an investor, the most common mistakes and no-brainers, and how to tailor your approach to investing. If you’re strapped for time, here are the

Key Takeaways

The quality of your information sources will determine the quality of your returns. Invest time into looking for credible sources.

Wasted attention is expensive. Guard it ruthlessly.

To guard your attention and improve results, match your dashboards to your objective and game. Your goals should inform your strategy.

Too much information is actually counterproductive. Identify the highest signal factors and reject the rest.

It’s easier to spot another person’s mistake than your own - So forming a community of trusted people will accelerate everyone’s improvement.

Stock picking is over-rated. Focus on portfolio construction instead.

Investing is about covering your bases rather than looking for brilliant decisions.

There is no risk premium without risk. Think of it as fees vs fines.

Human capital is the most important form of capital. Focus on growing it.

But I highly recommend you read the whole thing! It’s packed with useful information which will change the way you approach systematic learning.

Self-education

MS: Another area you’re passionate about is learning - I want to pick your brain on that. Some people jump into investing without studying it much, burn their fingers, and turn away. There are others who read the theory for years together and don’t even get started. What’s the right balance?

Kris: Start with a model portfolio suitable to your goals and risk tolerance. 60/40 isn’t necessarily horrible, but it’s not that hard to just go with a permanent portfolio. Use its performance to explore topics related to portfolio construction. Your asset allocation is the foundation of performance because inter-asset performance spreads are wider and less correlated than intra-asset.

But if you want to be a hands-on learner (or satisfy a gambling itch) have a laboratory for more speculative ideas, carve a well-defined percent of your portfolio for that and use those experiments to learn about interesting things (BTC, SPACs, closed-end funds, individual stocks etc).

MS: How can you learn about investing effectively and also validate it by putting it into practice?

Kris: a) Learn by reading and talking to good sources. How do you identify credible sources? That’s already a hard meta-problem. Charlatans are masters of blending in with well-meaning people and the intersection of well-meaning and competent is itself smaller than anyone wants to admit.

My friend Khe had me talk to a group of people that were aspiring personal investors. The feedback was that it was very helpful so maybe start there to see what credibility (I hope) looks like. It includes a reading list → Investing Q&A.

b) On validation: It’s a hard problem because the Signal-to-Noise Ratio is low. If the signal to noise were strong the strategy's capacity would quickly get filled or you are underwriting a risk that doesn't show up often. Validation is never fully possible in the same way that scientific inquiry never proves anything… It can be used to reject a hypothesis but not prove the success of any one theory. (This is really just a restatement of the black swan problem. No matter how many white swans you see, you can never rule out the possibility of a black one.)

Using the right information

MS: Another problem with investing is the deluge of information out there. How do you personally filter out the noise and design a feed that fits your investing approach the best? Do you have any advice for readers?