Discover more from Market Sentiment

Welcome to the 1,400+ investing enthusiasts who have joined us since last Sunday. Join 24,753 smart investors and traders by subscribing here. It’s totally free :)

I have a recommendation!

Nick Maggiulli is one of my favorite financial writers out there right now. He's been creating content on Of Dollars And Data for the past 5 years and recently came out with his first book, Just Keep Buying: Proven ways to save money and build your wealth. Apart from discussing strategies to start investing on the right foot, the book also gives a solid framework to think about how saving and investing fit into your life and career.

If you like evidence-based arguments about personal finance and investing, then Nick is the person to follow.

Sign up for his newsletter here or check out his book on Amazon.

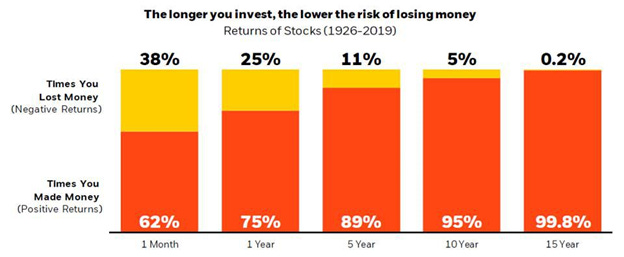

You have probably heard enough about the virtue of compounding by now. Market gurus extol the virtues of staying invested and focusing on the long-term horizon. It makes sense to set your sights on a goal that is years away because you are less likely to be perturbed in the short term. Many value investing acolytes start with similar intentions. After all, 15-year returns are almost always positive, right?

The catch is that if you’re new to investing and you’re on the left-hand side of the graph, you might not stay invested long enough to ever see those positive returns. Bull runs and bear markets are both triggered by the emotions of people like you and me, and denying our emotional side is not going to help. Instead, recognizing our fragility can set us up for success. Nowhere is this more relevant than when it comes to making a good beginning in investing.

A tale of two investors

Your personal experiences with money make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world, but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.

- Morgan Housel, “The Psychology of Money”

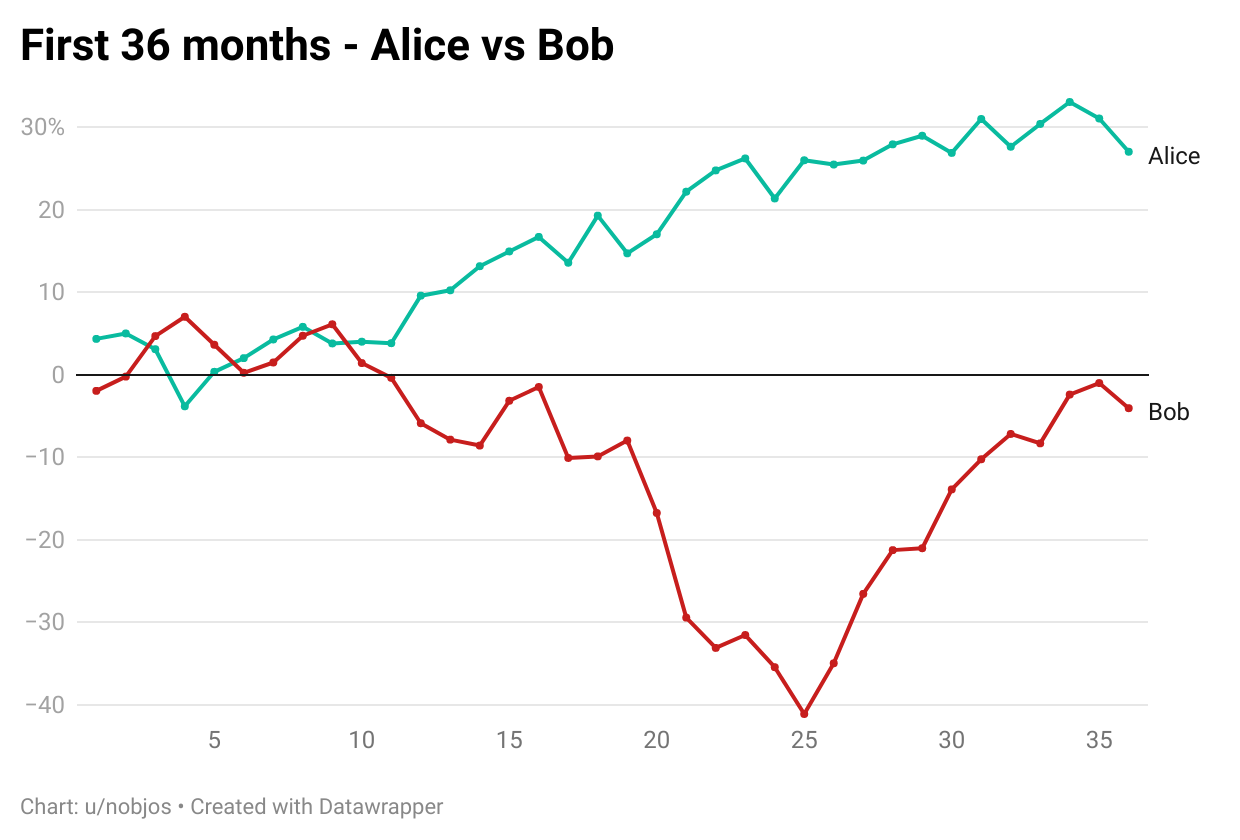

Let’s do a thought experiment: Imagine two new investors Bob and Alice who start investing in the market only 5 years apart. Bob starts investing in the stock market in January 2007, swept up by the euphoria of the bull market. But he’s a prudent investor - In spite of the rapid increase, he decides to invest only $100 in the S&P500 every month. But you know where this is going. The market crashes in 2007 and even though Bob continues to invest, his returns keep dropping.

On the other hand, Alice begins investing in 2012, and she follows the same strategy of putting in $100 a month. As luck would have it, it seems like the market has nowhere to go but up! In fact, Alice gets in at the beginning of one of the longest bull runs in history and she never has to worry about her returns.

Here are the monthly returns of Alice and Bob over the first three years of their investing:

Bob is off to a disastrous start - His portfolio is in the red 78% of the time, and his portfolio drops 41% in value at one point in time. Even though he has read that the market will bounce back in the long term, his conviction starts to wane. On the other hand, Alice’s portfolio has positive returns in 35 out of 36 months - and the only drop in value is by 4%!

At the end of their first 3 years of investing, Bob’s portfolio shows a 4% loss and Alice has gained by 27%. Bob stops thinking investing isn’t his cup of tea while Alice continues to invest.

But here’s the twist in the story: If Bob and Alice had both continued to invest, Bob would have had 213% returns in Jan 2022 compared to Alice who would have had 125% returns. Bob’s annual return would have been higher by almost 3% because he would have bought the dip. But is it any wonder if he had trouble sticking to his plan if all he saw was loss and panicking headlines in the first 3 years of his investing?

As it turns out, this isn’t an isolated occurrence.

Your experience shapes your investing

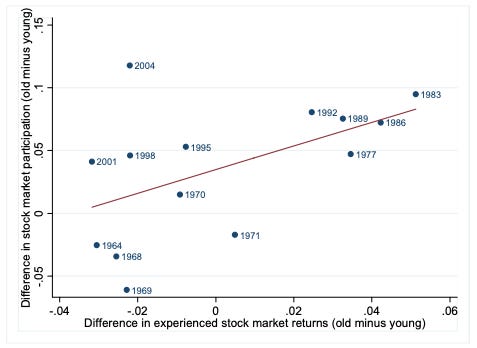

A study by Malmendier and Nagel of the NBER observed that older and younger generations allocated their wealth differently to the stock market based on their life experiences. The Y axis shows the difference in market participation between older (>60) and younger (<40) generations.

The surprising thing was that in spite of one of the longest bull markets in history in the 50s and a generally upward trend, the older generation just refused to invest in the market throughout the 60s. The reason was that this generation had entered the workforce during the Great Depression, and it had left a mark on their minds which lasted even 30 years later! The same could be true in the case of Japan - After the crash of 1989, the market has not regained its pre-crash peak so far and its citizens are still wary of equity investment.1

Due to the anchoring bias, the first experiences of people have undue weight in their own minds. Also, humans react more strongly to loss than the prospect of a gain. A 40% increase in the S&P500 is something to feel mildly happy about, but a drawdown by the same amount would set the alarm bells ringing and send you into panic mode. One way to deal with this is to dollar-cost average instead of investing as a lump sum. This distributes the risk across time.

Another way is to focus on risk-adjusted returns and diversify among different assets. By compromising on returns, you reduce the volatility in your portfolio and increase the probability of holding on for longer. We covered this in an earlier article.

But let’s say you have that part covered and want to maximize returns - Then the best strategy might not be seeking alpha in your beginning stages.

Saving vs Investing

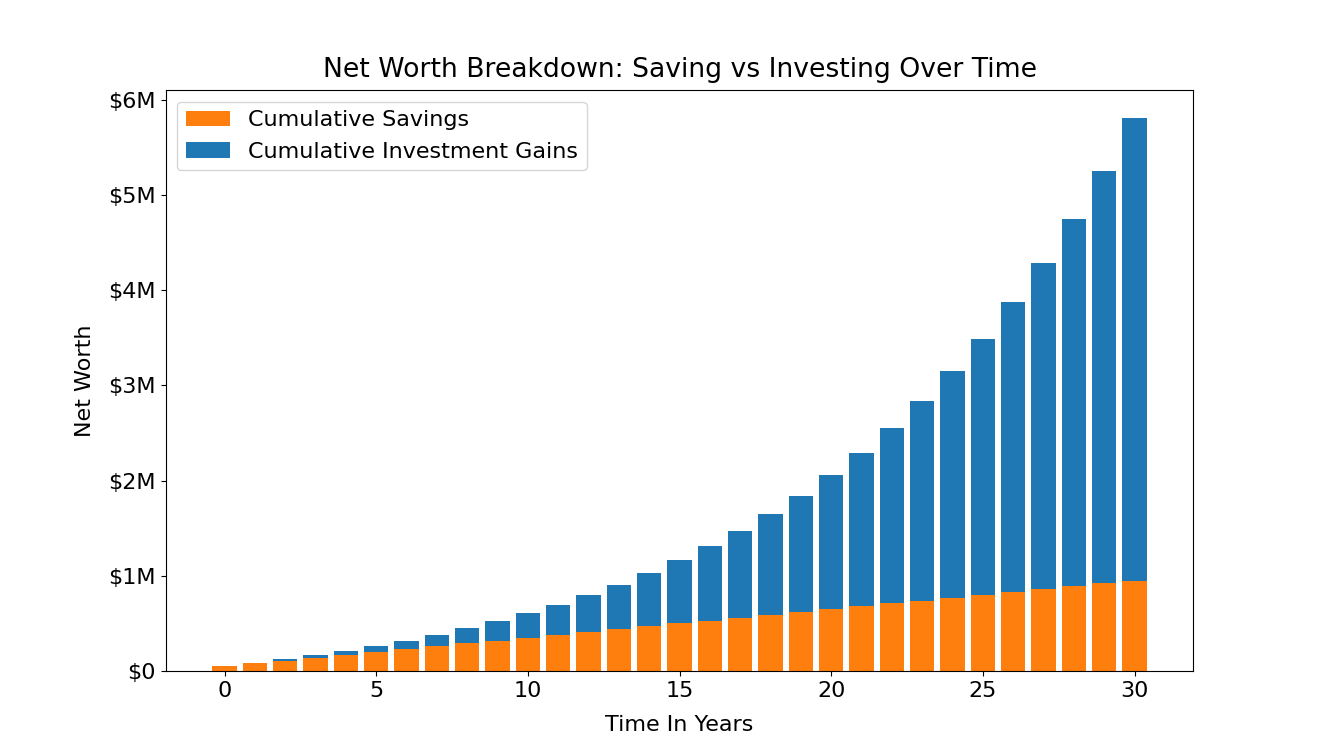

Think of investing as a machine that has two parts: The fuel which you put into it, and the engine which produces returns. The fuel in this case is how much you manage to save for the purpose of investing, but the engine is the process of generating returns, and the better your process, the more returns you generate. But the cool thing about investing is that the returns you generate can be added as fuel for the next round.

In the initial years of your investing, the fuel will be decided mainly by your savings. The returns will be a fraction compared to how much you put in. But as time goes by, the returns from the process will add up and eventually overtake what you can contribute from your savings.

While you can control the returns from your investment by a maximum of 1-2% annually (realistically speaking), you have far higher control over how much you save. By working towards increasing your income or cutting down on your spending in the initial years of investing, you can accelerate the point at which your investment machine will become self-sustaining.

Nick Maggiuli has a great article on his blog which dives deeper into this topic. As a rule of thumb:

If your total amount of assets x annual return is greater than how much you can save, then focus on maximizing investing returns. If your savings are higher, focus on increasing your savings instead.

For most beginners, this means focusing on increasing your savings.

So where does that leave us? Can we come up with a framework that gives us a good start with investing? This entire article can be summed up with a few basic principles:

Your initial experience with investing impacts how you perceive it.

The majority of your returns come from holding on to your investments. So you should set yourself up for success by increasing the probability of holding on.

You are likely to stop holding more due to heavy losses rather than inadequate gains. Therefore, protecting against the downside is more important initially.

In the initial stages, trying to maximize returns doesn’t add much value either. So focus on what you can control and concentrate on increasing savings.

This might seem like the opposite of common advice - After all, isn’t it advisable to take higher risks when you are young? Why not go all-in on a hype stock or crypto when you can afford to bounce back later?

What this fails to take into account is that a bad experience can alter your mindset enough to develop a revulsion towards the idea of investing itself. Protecting against that risk by diversifying, practicing dollar-cost averaging, constructing a sensible portfolio, and tuning yourself to stay in the game for the long run is what promises the most returns!

If you enjoyed this piece, please do me the huge favor of simply liking and sharing it with one other person who you think would enjoy this article! Thank you.

Disclaimer: I am not a financial advisor. Please do your own research before investing.

Footnotes

Subscribe to Market Sentiment

Actionable, data-backed investment insights for long-term investors, financial advisors, and analysts.