Discover more from Market Sentiment

“Every banker knows that if he has to prove he is worthy of credit, in fact his credit is gone” ~Walter Bagehot

Morgan Housel came up with the idea that there are three distinct sides of risk:

The odds you will get hit.

The average consequences of getting hit.

The tail-end consequences of getting hit.

The first two are easy to grasp. It’s the third that’s hardest to learn, and can often only be learned through experience. Say you are not wearing your seat belt – The odds that you will be caught are low (1) and even if you are caught, the fines that you end up paying are not too much (2). But the tail-end risk of getting into an accident while you are not wearing a seat belt (3), even though it has an extremely low probability is all that should matter.

Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) 48-hour collapse resulting in the second-largest failure of a financial institution in the history of the United States was a tail-end risk that none of us saw coming. SVB provided financing for almost half of the VC-backed startups in the U.S. and the company had more than $200B in assets and $175B in deposits at the time of its collapse.

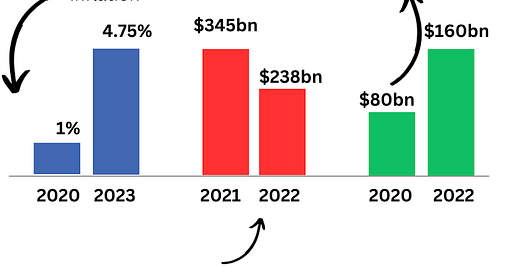

This is also deeply personal to us as SVB was the de facto bank recommended to us when we started Market Sentiment. In a stroke of extreme luck (hindsight is 20/20) they declined our application as we were bootstrapped.

Let’s dig into how one of America’s 20 largest commercial banks with more than $200B in assets went under in less than 2 days.

How does a bank work?

Let’s start with how a regular bank works. Contrary to popular belief, banks do not keep all the money that you deposit in the checking account with themselves at all times. They lend it out to others at a higher APR to others and they pocket the difference as profit.

How much they can lend out is based on the reserve ratio set by the Federal Reserve. If a bank has $1B in customer deposits and a reserve ratio of 10%, they are only expected to hold $100M in their accounts. The remaining $900M can be lent out to others. The money that was lent out again goes into other banks and the cycle repeats. The benefits of this system are apparent - You can cycle the same money through the economy multiple times and credit access becomes easier without creating additional money.

The problems of this system are also apparent – This puts the banks at constant risk of bank runs. What if all the customers return simultaneously and ask for their money back? Forget all customers, if more than 10% of the depositors demand their money in one go, we have a problem (If you think bank runs are rare, think again – they have occurred multiple times in the U.S)

The Govt. and the Federal Reserve have multiple safeguards to prevent this. First and foremost is the deposit insurance – If the bank you have put your money in is FDIC insured, deposits up to $250K are automatically insured. i.e, no matter what happens to that bank, you can be assured that you will not lose your deposit. Further, if a bank run actually happens, the central bank would step in and make a short-term loan to the bank so that it will remain solvent. In fact, the existing system is so robust that no depositor has lost a penny of FDIC-insured funds since 1933.

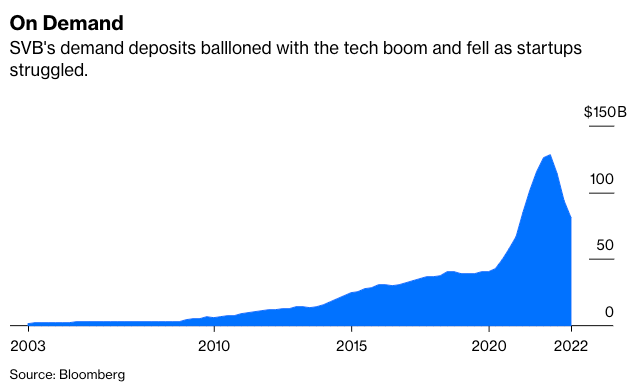

The good times

2020 and 2021 were incredible years for SVB. The record low interest rates, crypto/web3 boom, tech IPOs, SPACs, and VCs writing a check for every other growth company were all strong tailwinds for a bank that works exclusively with startups. Deposits in SVB grew from $60 billion in 2019 to over $189 billion in 2022.

One critical problem for SVB is that, unlike traditional banks that work with big companies, there aren’t as many credit-worthy startup customers to whom they can lend money. Exacerbating the problem was that Silicon Valley was swimming in cash during 2020 and 2021 and none of the startups wanted to take a high-interest loan.

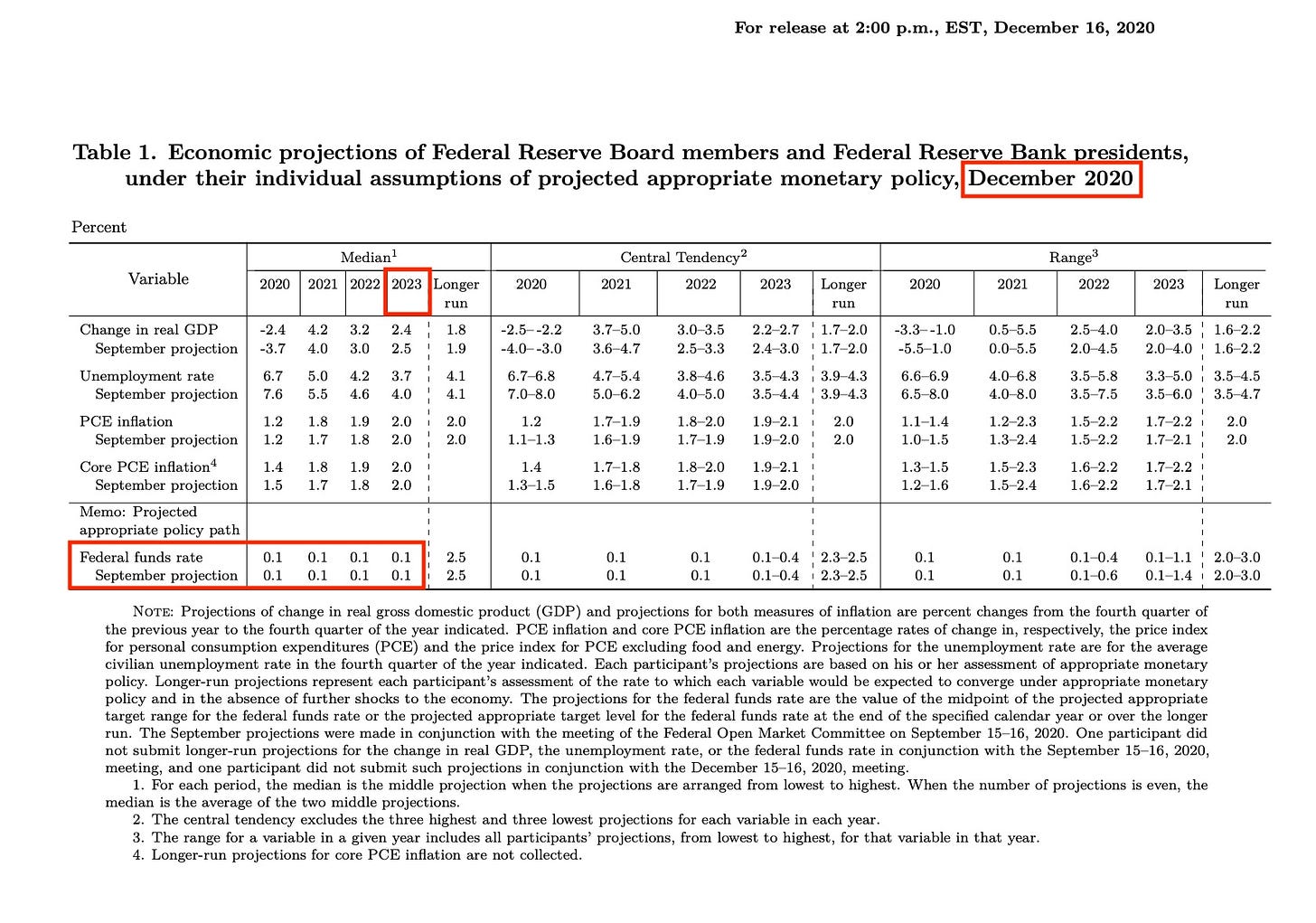

Even though they tried their best and increased loans by 100% to $66B, they still had far too much capital in their accounts that they wanted to deploy (remember – the difference is how banks make money). SVB bought $80 billion in Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) with an average yield of 1.5%. While it does look extremely foolish now, you have to remember that at that time, the interest rates were near zero and Fed’s projected interest rate was 0.1% for 2023.

The perfect storm

SVB’s trouble began with the Fed raising interest rates at the fastest pace we have seen in recent history to contain inflation. The rate hikes were a triple blow to SVB:

With every rate hike, the $80B SVB had locked up went down in value. A 1.5% yield might look attractive when the interest rates are 0% but with Fed rates approaching 5%, the bonds had a drastic drop in value. The bank had mark-to-market losses of $15.9B as of Q3’22 (still unrealized but we will come to why this was important later).

With the end of zero-interest periods, growth stocks started dropping like flies, IPOs dried up and VC funding became nonexistent. That meant that the inflow of new deposits became a trickle at SVB which exclusively catered to startups.

To make things worse, deposits started to fall. Companies started withdrawing as they were not getting any new funding, and cash burn was increasing given the higher inflation and lower customer demand.

The final straw

Investors were already aware of the increased stress on the bank. To fund the redemptions, SVB sold a $21 billion bond portfolio on Wednesday - forcing them to realize a $1.8 billion loss as their portfolio was yielding an average of 1.79%, far below the current 10-year Treasury yield of around 3.9%.

Just the next day, SVB announced that they were also selling $2.25 billion in common equity and preferred convertible stock to fill its funding hole. This was a really bad move. The market was already spooked by the collapse of the Silvergate bank and SVB announced a raise with a press release that was all numbers and no narrative. The company made no mention of why it was raising money, how it was planning to use it to strengthen its balance sheet, and how strong its financial position was.

SVB dropped their biggest, most intricate, most unnerving news of the year — without any meaningful reassurance to their core customers (startup founders, especially early stage) and the people they listen to the most (influential VCs) - Lulu Cheng

This spooked a lot of founders who had almost all their cash with SVB, and VCs jumped in to advice that founders get money out as soon as possible. This triggered a bank run as customers tried to withdraw a whopping $42 billion from the bank in one day.

What now?

SVB has been closed by California regulators and taken over by the FDIC. But the problem is that FDIC insurance covers only up to $250K and 97.3% of customers have more than that in their accounts.

We believe that this shouldn’t be an issue and FDIC is exceedingly efficient at returning customer deposits. The order of priority for FDIC is

Insured depositors > Uninsured depositors > lenders > equity holders

Since the IndyMac failure in July of 2008, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. has, whenever possible, protected uninsured depositors in failed banks from any loss - American Banker

When Washington Mutual failed in 2008, all deposits were transferred to JP Morgan which acquired WaMu for $1.9 billion. No one lost any money that was deposited in Washington Mutual Bank & no deposit insurance was used. It would probably be a scenario like this where FDIC arranges a sale by Monday and depositors are made whole by the end of the week.

There is too much riding on this for FDIC or the Fed to risk not returning the money to depositors as a lot of companies would be unable to make payroll and it would an extinction-level event for startups.

As Matt Levine so eloquently put it,

If it turns out to be true that they lose their deposits, there could be more bank runs: Lots of businesses keep uninsured deposits at lots of banks, and if the moral of SVB is “your uninsured transaction-banking deposits can vanish overnight” then those businesses will do a lot more credit analysis, move their money out of weaker banks, and put it at, like, JPMorgan. This could be self-fulfillingly bad for a lot of weaker banks.

Market Sentiment is now fully reader-supported. If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and consider upgrading your subscription to get access to all issues (the last 3 premium analyses - Investing in small caps, Using consumer sentiment to time the market, A case for strategic mediocrity using the 60/40 portfolio).

Disclaimer: We are not financial advisors. Please do your own research before investing.

Great piece

“How did you go bankrupt?" Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” ― Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises.