Discover more from Market Sentiment

Successful investing is simple, but, boy oh boy, it ain't easy. - Jim O'Shaughnessy

Stanford professor Alex Bavelas designed a fascinating experiment in which two subjects, Smith and John, are facing individual projection screens. They cannot communicate with each other and their task is simple — to identify the difference between healthy and sick cells.

Both of them are not trained to do this and must learn on the go to identify which cell is healthy and which one is not, purely by trial and error. Every time they guess, a signal will flash indicating whether they were right or wrong.

The catch is that only one person (Smith) gets the true feedback. If he is correct, the light flashes that he is right and if he’s wrong, it flashes wrong. Since Smith is getting true feedback on his picks, he starts instantly improving and then starts getting around 80 percent of his guesses right.

John on the other hand is completely lost — He doesn’t get true feedback and gets feedback that’s almost random1 for his picks. But, since John does not know this, he tries to make sense of what’s happening and starts trying to find patterns in his picks.

When the professor asks both of them to discuss the rules they use for separating out healthy cells from unhealthy ones, Smith, who got the correct feedback offers a very simple but concrete explanation of how he is separating the cells. John, on the other hand, suggests a highly complicated logic that’s nuanced and takes into consideration a lot of factors.

Where it gets interesting is that Smith doesn’t think John’s explanations are absurd — He is impressed by John’s brilliance and feels inferior due to how simple his own rules are. When they are asked to repeat the experiment again under the same conditions, John does not improve, which is expected since he is still not receiving the correct feedback. But Smith (who got the correct feedback both times) starts doing considerably worse since he is trying to fit John’s complicated model into his predictions.

True experts in their field can make any concept look simple. Look at how Richard Feynman breaks down why two magnets repel or how Warren Buffett explains his business empire and his investment decisions through Berkshire’s shareholder letters.

On the other hand, if you talk to day traders, they direct you to these complicated patterns2 that they say will help them make money.

We almost always equate complexity to a better product — Think of the number of times you were impressed by a friend or colleague introducing an idea with a lot of complicated jargon and terminologies. You come away from the conversation more confused than you went in but you end up thinking that the person is an expert and you should trust him/her.

Since this type of selling complexity is exceedingly common in investing, we have decided to put together 5 simple & timeless rules that can form the foundation of successful long-term investing.

1. Don’t spend more than you make

Even if you can invest like Warren Buffett, if you can’t save, you will die poor - William Bernstein

If there is one rule that you should know in investing, it should be this — No matter how much you optimize your investments and maximize your returns, it doesn’t matter if you spend more than what you make. You should always live below your means and be mindful of how you spend your money.

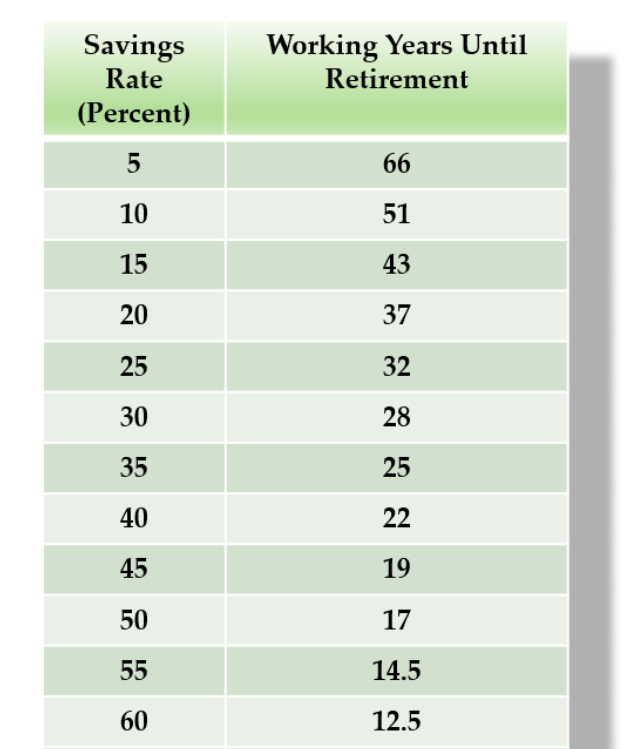

If you spend 100% of what you make, then you will never retire. How long you will work before you retire is simply based on your savings rate. If you are only saving 10% of your salary by the end of the month, you will have to work 51 years until your retirement. If you bump up the savings rate to 25%, you can be done in 32 years. This is why saving (and investing) is so important.

2. Plan on living a long time

Here’s a fun quiz:

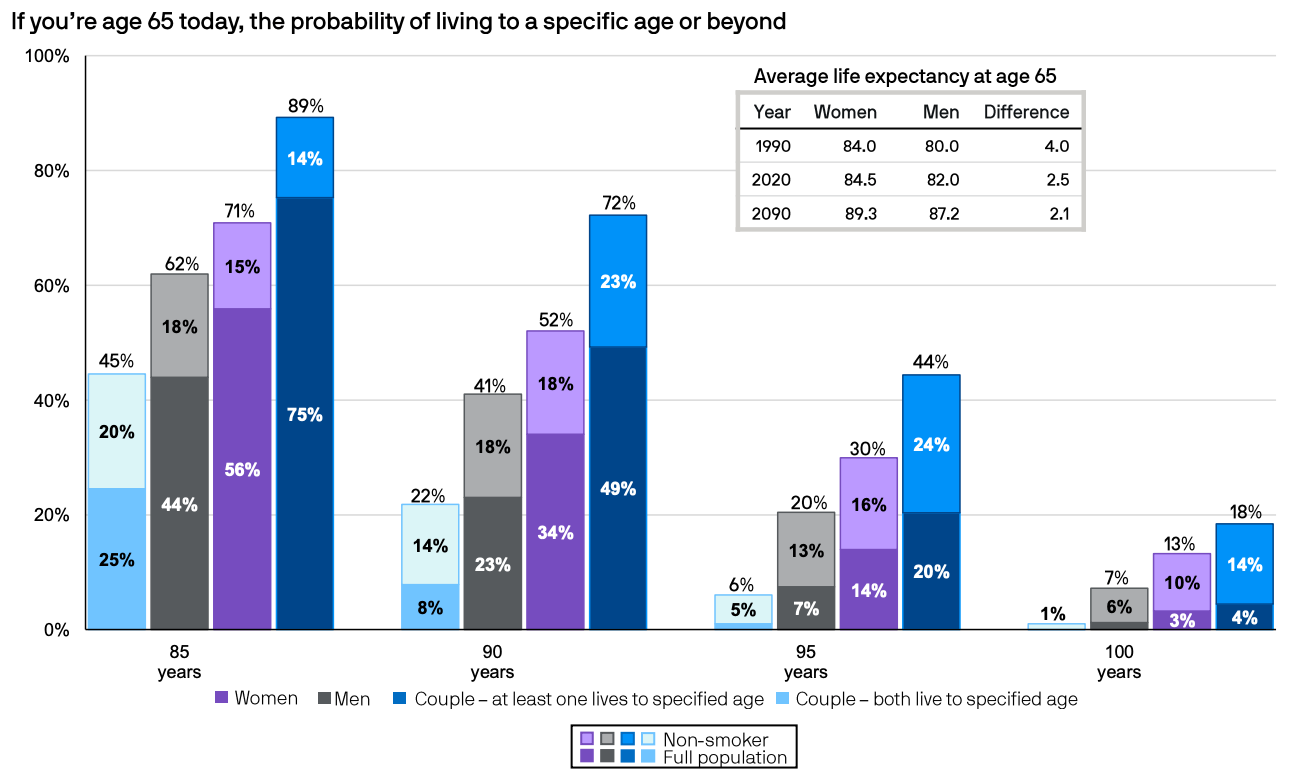

We will get to the answer in a while. But, the simple fact is that we are all living longer and longer due to breakthroughs in medical technologies. The average life expectancy for a 65-year-old today is 83. By 2090, it’s expected to climb to 89.

Coming back to our poll, there is nearly a 50% chance that one of the partners will make it to their 90s. So considering that you will retire at 60, you should plan your portfolio so that it can easily last you 30+ years!

3. Invest & Diversify

High risk and high returns go hand in hand and so do low risk and low returns. It’s easy to overestimate your risk tolerance when the times are good.

Just take a look at the chart above — Just in the last 50 years, we have had 3 different occasions where the stock market lost ~50% of its value. While it looks simple on a chart, you need to be brutally honest with yourself if you would be comfortable holding on to your portfolio after it has been put through the grinder.

If you are comfortable taking that extra risk, you are rewarded long-term. Small-cap stocks which are considered riskier than large caps have returned more over the past 30 years. Bonds and T-bills on the other hand had lower volatility and lower returns. As they say, you can't have your cake and eat it too.

4. Fees Matter

Buffett once made a $500,000 open bet

“No manager can choose a set of at least five actively managed funds that would beat the Vanguard S&P500 index fund after fees, over one decade.”

Ted Seides was the only person who answered the call, and he selected five funds-of-funds. Despite a neutral market environment and the huge financial incentive to do well, the five funds averaged 2.2% in returns against the index fund’s 7.1%. And this was even before fees were considered – 60% of all gains were diverted to the two levels of fund managers!

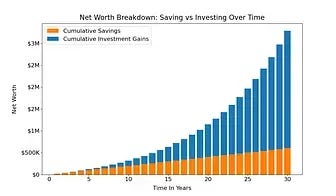

Buffett ended by saying that there are definitely competent managers out there who justify their fees, but the problem is in finding them among the thousands of registered professionals. For someone who starts investing at 25 and retires at 65, a 1% reduction in expense ratio can increase their savings by $220K giving almost 10 years in extra spending3.

So unless the fund can consistently beat the market over a 40-year period (which is very unlikely), the investor is bound to make a lower return than his peer who invested in a passive fund.

5. Stay the course

There is a reason the story of the Vanguard Group is titled Stay the Course. Once you adopt an investing plan, you should stick with it no matter what. Here’s the story of the world’s unluckiest investor ‘Bob’.

Bob made his first investment in the beginning of 1973, right before a 48 percent crash for the S&P 500. Bob then held onto stocks after the drop, saving a total of $46,000, and not getting up the gumption to commit more savings until September 1987—right before a 34 percent crash. Bob then continued to hold tight, making only two more investments before retirement, which came right before the 2000 crash and then the 2007 crash!

Even after all these misfortunes, Bob actually made money. He turned his $184K invested into $1.6M → an annualized return of 9%. The simple secret behind Bob’s success is that he never sold his investments.

Since 1950, no matter how you built your portfolio with stocks and bonds, if you had held for more than 20 years, you would have always come out ahead.

Incremental benefits of holding long-term are that you will have a lower tax rate on your gains and significantly lesser transaction costs. Staying invested also makes sure that you don’t miss out on the best days in the market.

Sit on your ass. You’re paying less to brokers, you’re listening to less nonsense, and if it works, the tax system gives you an extra one – Charlie Munger

Putting it all together

In summary, to be a successful investor you just need to

Spend less than what you make

Plan for a long retirement

Invest in diverse assets

Optimize for the lowest possible fees

Stick to the plan

Each of these principles is vital, though they are most effective when used together. When asked about his job as the writer of a finance column, the legendary writer Jason Zweig once said:

Good advice rarely changes, while markets change constantly. The temptation to pander is almost irresistible. And while people need good advice, what they want is advice that sounds good.

The investor’s biggest enemy is likely to be himself, so a large part of successful investing is not in finding the “right” investments, but rather in developing a process and mindset that lets you stick with the principles above.

Let me know below how you resist the pull of your emotions, and what your experience with these principles has been.

Footnotes

Technically John is not getting purely random feedback. He is getting shown whatever Smith is picking with no relation to what is being shown to John. We found this study from this excellent Twitter thread by Jim O'Shaughnessy.

While we are not rejecting these claims outright, we are yet to see any statistical evidence whatsoever to prove that these patterns can reliably generate alpha.

The saving phase simulates a participant with a salary of $45,000 at age 25, linearly increasing to $85,000 by age 65, making yearly contributions of 6% of salary at age 25, increasing by 0.5% per year to a maximum of 10% and with a 50% company matching contribution up to the first 6% of salary. In retirement, $63,750 (75% of the final salary) is deducted at the beginning of each year. The blue-shaded area shows ending savings with an after-cost investment return of 9% assumed at age 25, linearly decreasing to 6% at age 80 and remaining constant thereafter. Inflation is assumed to be a constant 3%. The tan-shaded area assumes a 1% greater return each year due to reducing the costs of investment by 1%. All amounts are in present-day dollars.

Just a reminder that Market Sentiment is now fully reader-supported. If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the like button and consider upgrading your subscription to get access to all issues.

(We are offering a 20% discount on our annual subscription)

Disclaimer: We are not financial advisors. Please do your own research before investing.

Subscribe to Market Sentiment

Actionable, data-backed investment insights for long-term investors, financial advisors, and analysts.

Good, (not so) common sense advice in this deliberately over complicated world.

Great write-up—thanks!